Years ago, I wrote about Component-based Game Design, in which I talked about the advantages of breaking down your game objects into components. Inspiration came from a number of places, including:

My Experience

Over four years ago, I even managed to implement a simple test program as part of my application for my last day job, and at the time I thought it was easy and fun to do. The hardest part was setting up all of the basic infrastructure to support registering components.

In four years, however, I never wrote code that resembled that test program.

Why not? Because it turned out that it wasn’t all that easy or fun, and I didn’t like the idea of making a full game with it because even a small test program was a bit painful to build up. My implementation of a board game was heavily based on Hannah’s concepts of States and Actions, so it might be a bit more complex than what is typically considered the state of the art. Actually, it’s probably more accurate to say that the implementation was based on my understanding of Hannah’s article, so I probably did things terribly wrong and made it more painful than it had to be.

Each Action typically interacted with multiple States, and so there was a lot of dynamic_cast calls. Practically speaking, adding a new State and its associated Action meant a lot more work than I would have liked. I might as well have stuck with the monolithic game object, and in the years following my original post on the topic, I pretty much did. Most of my projects were small in scope and had very specific designs that didn’t change much, and the code base was manageable enough that it wasn’t a problem when the designs did change.

The Motivation

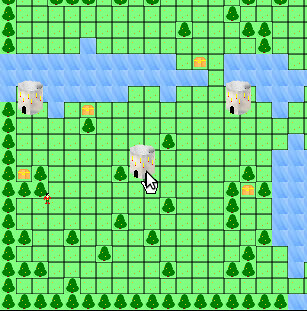

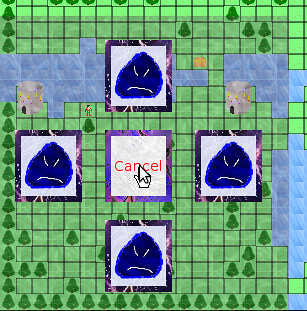

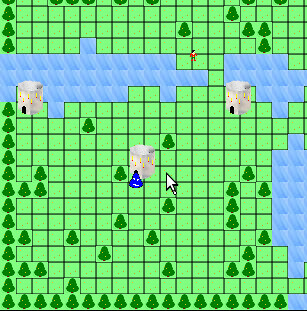

With Stop That Hero!, I wanted the flexibility to change the design of the game as it was being developed. That isn’t to say that I wanted the ability to make a first-person shooter halfway through the project, but I did want the option of experimenting with new monster types, different player actions, and objectives for a level. I want to be able to change the design of the game without requiring me to change the code drastically. I also wanted the ability to drive the game through the data, which would allow me to create custom scenarios and interesting game experiences, and it would allow players to create their own mods.

I already understood the basic concept of component-based game objects. Instead of monolithic, inheritance-based objects that are hard to change, objects should be identifiers with the components that make up an object being tied to that object identifier. If the design changes, the impact on the project might simply be the assigning or removing of components. For instance, I could have enemies that walk on land or fly in the air. I could introduce a new amphibious enemy by assigning it the ability to walk on land and create a new component related to swimming in water. The code involved is minimal and low-impact on the rest of the project.

What I didn’t understand was how to go about implementing a component-based game object system that wasn’t cumbersome and annoying to use. In my experience, having ready-made components was great for game design, but creating the components and the system to use them was a pain.

The Research

And so, once again, I find myself looking into component-based game design. I found quite a few more resources over the span of a few days as well as some that I have read in the last few years. I’ll quickly list them in case you’re interested in pursuing this topic yourself:

Terrance Cohen’s presentation led me to discover that Insomniac Games has a public-facing research and development page, which led me to his presentation Three Big Lies: Typical Design Failures in Game Programming, which introduced me to the concept of data-oriented design.

And from there, I realized I needed to clarify what it was that I was looking for.

I wanted to learn how to do data-driven, component-based game development in a relatively simple way. What I realized was that I was looking for three different things that had little to do with each other.

One, I wanted my game to be data-driven, which isn’t all that hard. So long as the game is pulling in data from somewhere and acting on that data, it’s data-driven. It’s possible to have the inheritance-based hierarchy of game objects and still run the game based on external data, and it’s possible to use that external data for component-based systems.

Two, I wanted my game design to be easy to change. A component-based system is superior to the inheritance-based one in this regard. With an inheritance-based system, any design change might impact the carefully-planned hierarchy. It can quickly be hard to manage, and changes become more and more painful. Components are easier to change. Add them or remove them, and an object’s behavior changes, and it works on the fly as well.

Three, I wanted to figure out how to write the code for such a system without the complexity I dealt with last time. Seriously, dynamic_cast everywhere a component needed to talk to another component made the creation of new components quite painful. There had to be a new way.

Data-driven games are much more powerful with a component-based system, but it’s outside of the scope of what I want to focus on here. What I was most interested in was the answer to the question “What is the best way for me to implement a game object in my game?”, and frankly, it wasn’t enough to know I wanted components aggregated together. I wanted to know how.

Which brings me back to data-oriented design. According to DOD, the only purpose of code is to transform data. That’s it. Traditionally, programming was focused on algorithms and code, modeling the problem in terms of classes and objects. The problem is that the models tend to add more complexity to the original problem of modifying data.

Now, data-oriented design isn’t the same thing as data-driven design. The former is about programming, while the latter is about game design. See Noel Llopis’ Data-Oriented Design (Or Why You Might Be Shooting Yourself in The Foot With OOP):

OOP is so ingrained in the current game development culture that it’s hard to think beyond objects when thinking about a game. After all, we’ve been creating classes representing vehicles, players, and state machines for many years. What are the alternatives? Procedural programming? Functional languages? Exotic programming languages?

Data-oriented design is a different way to approach program design that addresses all these problems. Procedural programming focuses on procedure calls as its main element, and OOP deals primarily with objects. Notice that the main focus of both approaches is code: plain procedures (or functions) in one case, and grouped code associated with some internal state in the other. Data-oriented design shifts the perspective of programming from objects to the data itself: The type of the data, how it is laid out in memory, and how it will be read and processed in the game.

One thing that wasn’t clear to me while doing all this research is that data-oriented design is not terribly compatible with object-oriented programming, and since most of us game developers know OOP as THE way to program, it’s difficult to see it any other way.

The thing is, it isn’t a normally a problem. OOP can still get you to a correct implementation, especially when performance isn’t your primary concern. The code will run the way it is expected. One of the major advantages touted by all of the data-oriented design articles I found was efficiency. As an indie game developer who doesn’t work on games that push the processor or memory requirements of my customers’ machines, I’m not usually worried about cache thrashing or performance issues. I’m not concerned about throughput on PS3 Cell processors or processing shaders quickly on the GPU. I’m not one of those people who thinks that processor speed is fast enough and memory is large enough for whatever horrible implementation I can come up with, but at the same time, I am not using the Crysis engine and gigabytes of data for my games. I don’t currently make games that take advantage of parallel processing and I most definitely wasn’t going to worry about the cost of calling virtual functions, so initially data-oriented design wasn’t very appealing.

But why I kept pursuing information on it was that it was supposed to be great for unit testing and modularity. Since I’m a big fan of unit tests, being able to write them more easily and with less dependencies would be a huge win. Being able to write simpler code would be another huge win because it can help in the creation of components.

So bottom line: data-oriented design looks like a fantastic way to help me develop a game object system. The code will be simpler and easier to test, and I get the extra benefits of having more efficient code! Nice!

Well, at least at a high level. I still need to figure out what it all means when I don’t have the benefit of an existing company’s proprietary engine. I figured that I needed to explore this data-oriented design thing a bit more.

EDIT: Here’s a talk by Andrew Kelley with practical ways to implement data-oriented design: Andrew Kelley – Practical DOD

The first three examples helped me understand how the actual code might be laid out, but it was that last one that really made me understand where OOP is causing problems. It focuses mainly on performance problems related to caching, but the idea of performing a bunch of unrelated actions on a single object at a time versus doing one action for lots of objects at once was really made clear, especially after seeing images 12 and 30-32.

The Frustration

Unless you’re one of the mainstream game developers who have used or implemented a component-based system as part of your job, it seems getting started is the hard part. Game development forums have a number of threads in which people are convinced of the benefits but don’t know how to get a system built.

The article in Game Programming Gems 5 by Bjarne Rene has sample code on the book’s CD, and the good news is that it is a complete solution, but it seems that the complexity of inter-component communication can be a problem. Plus, is it still relevant? It seems as if game developers have moved away from components that perform actions, at least according to what I’ve read.

I haven’t had a chance to look at Game Programming Gems 6, but apparently there is an article on game objects there as well, although it sounds like there is no example code so I’m not sure how hard it would be to follow. The blog T=Machine argues that there is a difference between Entity Systems and component-based systems. Fine, but your entity system is still aggregating components, so regardless of the differences, I need to know how to create a component system.

It seems that anytime there is code in any article or presentation, it’s incomplete or hard to follow. The article might say that you should use IDs and not create an actual object class, and yet the example code has a class. It might show a class deriving from some base that was never introduced or create a function signature without an explanation for why it is there. I almost wish the articles would unit test their way through their sample code just so I could follow along with the author’s intent. Also, it seems that there is no shortage of article series on the subject that never get finished. Some examples are MMO-specific, some are concerned about performance, and none seem straightforward. One article will suggest doing something that another says you shouldn’t do.

And so I felt like pulling my hair out when I sat down to try to implement my own system. At a high, conceptual level, it makes sense to me that an object is nothing but an ID, and it’s the components aggregated together that make up a game object. I understand that I should be able to create an object by creating components, associating them with the object ID, and adding those components to some manager. What was difficult was implementation, and part of the difficulty was about ownership of the data.

I had written an entity manager with a couple of components, only to throw it away after becoming frustrated with how limited it was. I apologize if you’ve read this far and were hoping for more insight into a component-based system. It was too much for me at this time, and I had to stop if I wanted to make progress on my game.

Ultimately, it seems that the component-based system isn’t going to happen, but I need to figure out how to make progress on the game itself. Somehow, in learning a lot more about components, entity systems, and data-oriented design, I feel frustrated and incompetent. Every time I want to write code, I have a dozen different alarms going off in my head warning me that what I want to do isn’t what this author suggests or is against what that author says. My existing code, which I was happy with before, is now feeling too constricting. Whenever I try to make progress, I feel like I have game developer’s block. I can’t see the next step, and even when I think I have, I don’t know how to start. It’s a bizarre feeling.

This post came off more whiny than I would have liked, but I’m not blaming anyone or feeling entitled. I’m just frustrated, and I’m trying to figure out why.