Note: this post was originally published in the January 2012 issue of ASPects, the official newsletter of the Association of Software Professionals.

You’ve been working on your action game for so long that you’re sick of playing it. You have a wide variety of enemies with different strengths and weaknesses, and you’ve provided the player with dozens of different weapons to take advantage of those weaknesses. You’ve tested so many different playstyles, changing variables as you found issues, and you even had your family and friends try it out to make sure that they don’t think it is too hard or too easy. Your game is ready for your first customer!

Except something goes wrong. Someone discovers a way to use a weapon that dominates all of the enemies in your game, eliminating the challenge and fun entirely. Or perhaps there’s a sequence in the game that you find slightly challenging, but to someone who doesn’t know all of the intricacies of the game and hasn’t had the opportunity to practice for months, it’s frustratingly too hard. In either case, the reason why your game isn’t ready is that it isn’t balanced.

A Numbers Game

Balance in a game can refer to many things, but the basic idea is that you are deciding what values and numbers to use in a game. As an example, Tic-Tac-Toe, or noughts and crosses, has two players, nice spaces in a 3×3 grid, the requirement that you can place only one ‘X’ or ‘O’ during a turn, the requirement that each space can only hold one mark, and a victory condition of having three of your marks in a row. Tic-Tac-Toe is a fairly simple game, but you can imagine all of the ways you can upset the balance by changing these values. It would be a completely different game with a 4x4x4 matrix and requiring four in a row for a victory condition.

Balancing a game requires getting the numbers right, but it’s not always obvious what “right” is. Should your strategy game have one type of resource to collect or two? Should a unit that does twice the damage of another unit cost twice as much to produce? What if it has half the armor?

As I was getting my strategy game “Stop That Hero!” ready for release, I tried to make sure that even if someone didn’t play perfectly, they would still be able to win while also ensuring that it wasn’t too easy to win. What I found was that even when I played how I thought was sub-optimal, it was still using special knowledge that I had as a developer, so what was somewhat challenging to me was way too hard for someone else. Having other people play it gave me a lot more information to go on.

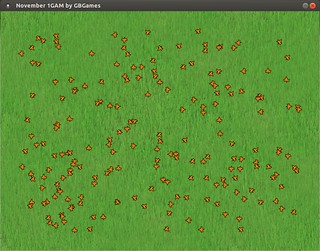

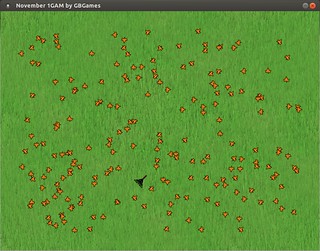

The feedback you get with playtesting will be invaluable, but you might find you are making guesses at appropriate values. In my game, the player summons minions such as orcs and dragons to fight off heroes such as archers, knights, and wizards. Summoning costs resources, and it takes time to summon a minion. How much should an orc cost? How long does it take to summon a warlock?

While guesses are good for getting the game up and playable in the first place, the guess-and-pray approach can be tedious and slow when you’re trying to get the game ready for customers. There has to be a better way.

A Little Analysis Goes a Long Way

I found two tools helpful in game balancing work: a spreadsheet and a whiteboard.

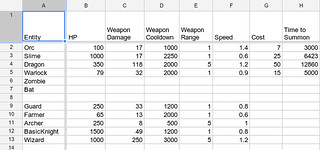

In the spreadsheet, I entered as much information about the various entities as I could. Data such as HP, movement speed, and minion costs all ended up in the chart. In the game, resources increase by 1 each second for each castle and tower the player controls, so time is another value to keep track of.

Using numbers such as cost, time to summon, game play time, and the number of towers the player controls, you could answer some questions, such as:

With control of one tower, how many orcs can the player afford by the time one orc is available on the battlefield?

How many slimes can be summoned after 30 seconds of game play if the player has control of one tower? After 1 minute? With two towers?

How many orcs could have been produced during the time it takes to produce one slime?

The answers come fairly naturally from the data. For instance, if an orc takes 3 seconds to be summoned, and a slime takes 6.4 seconds to be summoned, you can produce two orcs and part of a third in the time it takes to produce one slime. Knowing this information, you can determine that the cost of one slime should be just slightly more than the cost of producing two orcs, all other things being equal.

But sometimes the values aren’t equal. In my case, an orc does the same damage as a slime during one attack, but orcs deliver attacks every second while a slime needs to spend a little more than 2 seconds to do its next attack. Also, slimes move at less than half the speed of orcs. On the other hand, slimes have ten times the hit points, making it much harder for the heroes to kill it. So how much is a slime worth compared to an orc now?

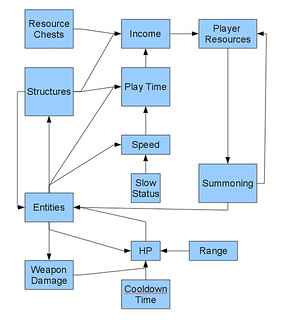

If you can come up with appropriate formulas, you can gather some statistics to help in balancing. Figuring out the relationships between all of these numbers is key, and this is where a whiteboard can come in handy.

This chart represents all of the interacting systems during a game session. You can see how player resources are influenced by play time, the structures owned by the player, and resource chests collected. More resources means more minions can be summoned, which decreases resources and increases the number of entities. Some entities can capture towers, which helps increase resources. Combat is represented by the weapon-related boxes at the bottom of the chart, which all impact HP, which impacts whether or not a given entity exists. Speed can be impacted by a slow status effect, which means heroes take longer to move, which means the player has more time to gain resources and summon minions.

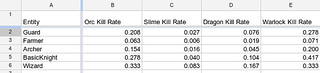

Even with only a handful of numbers, you can see that the relationships between them and across systems can get complex. Still, this chart helps us find our way to some interesting statistics. For instance, we can determine how many orcs it takes to kill a one guard. Let’s say that guards have 250 HP and do 33 HP of damage every 1.2 seconds, and orcs have 100 HP and do 17 HP of damage every second.

Orcs take (250 HP / 17 HP damage) x 1 second = 15 seconds to kill a guard. Guards take (100HP/33 HP damage) x (1.2 seconds) = 4.8 seconds to kill one orc. Since guards kill orcs at a rate of 0.208 per second (1 / 4.8 seconds), it takes 15 seconds x 0.208 = 3.125 orcs to kill a guard. In game terms, three orcs will die before the guard’s death blow is dealt by the fourth orc.

Knowing this information, we should make sure that the player is capable of summoning at least four orcs for every guard in the game world, or else it will be impossible to withstand the onslaught of the heroes. If orcs cost 7 resources, and if one level is designed to produce four guards from the nearby village, the player should be able to have 7 resources per orc x 4 orcs per guard x 4 guards = 112 resources before those guards arrive.

You can also see what happens if you change a number. If an orc does twice as much damage, it would take 250 HP / 34 HP damage) x 1 second = 7.4 seconds to kill a guard, so it would take only two orcs to kill a guard (7.4 seconds x 0.208 orcs killed per second = 1.5 orcs).

By studying the relationships between numbers, you can determine what information would be useful, and then simple mathematics can get you that information. Spreadsheets also help you by making it easy to tweak values to see what effect a change might have on other values. You still need to playtest as much as you can since it is only by playing that you can determine if the game is entertaining enough, but this article should have demonstrated that you have tools to aid you in balancing the game.