Mike Kasprzak wrote about his five years as a full-time indie, and it’s a fantastic read. Especially fascinating was how long it was before he made Smiles and his first real income. After years of burning through savings, suddenly things came together for him, and he was winning prizes and being pretty awesome.

In contrast, I’ve been running my business officially for almost five years, but I’ve only been full-time since the end of May. On the one hand, that means my story won’t be nearly as fascinating or interesting as Kasprzak’s, but on the other hand, existing part-time indies aspiring to make the jump to full-time might appreciate reading how things look for me in the short term.

I wrote about some of the reasons why I went full-time indie, but part of it was freedom. Spending 40-60 hours a week on stuff unrelated to my business meant I was giving my business short shrift. I spent so many years learning about game development, but I could only dedicate a few spare minutes to actually doing it? It wasn’t right. So I quit the day job.

Ah, Freedom!

Did I hit the ground running? No. The World Cup was starting, and I was going to watch as much soccer as I could!

I was even writing about it at my new website, Modern American Soccer, which actually got quite a bit of traffic in the weeks leading up to the first game due to the US Central-time specific calendar I created on Google. In fact, that site was going to advertise the soccer-based social networking game I was going to create with a colleague before that project fell through, so it was related to my games business initially.

Either way, my first month as a full-time indie game developer was spent getting used to not having a day job to worry about. I knew that it meant a month of spending my savings with nothing to show for it, but I decided at the time that it was acceptable. I was taking a break and getting my bearings (and watching soccer).

Now What?

When I finally sat down to do real work related to my business, I found it frustrating to not know what I was doing at any given moment. Not knowing when my next infusion of income was coming from made me feel a bit antsy, and yet I felt a bit overwhelmed by the number of different tasks to accomplish. I wrote about how it felt in the article Clear Goals or Trivial Pursuits, and I realized I needed to define some specific goals to tackle, or at least pave the way to learning what those goals should be.

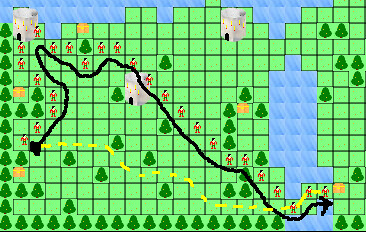

In July, I hosted MiniLD #20 with the theme Greed and the special rule “Only One of Each”, which was meant to discourage people from reusing content and code. It was one of the more successful MiniLDs, with plenty of submissions, but my game wasn’t one of them. My project, The Old Man and the Monkey Thief, was the first game development project I started since quitting the day job, and I didn’t finish it in time.

It was the first game I’ve made that involved a scrolling screen, and I remember feeling incompetent. How can I have thought that I could be a full-time indie developer when I didn’t even know how to make a game with something as basic as a scrolling background? It was a scary thought. Had I made a huge mistake? Was I not as prepared for making a go at a game development business as I thought I was?

Again, one of the reasons why I went full-time was so I could dedicate many more hours towards my games. If I felt incompetent, it is because I didn’t spend nearly as much time on it as I should have, and now is my chance to do otherwise.

Setting Monthly Goals

I decided that August would be the month that I would try to complete three small games in an attempt to learn as much as I could as quickly as I could.

My first project was my MiniLD game, which was taking me much longer than I expected, partly because of how unique everything had to be in the game. I didn’t finish it until right before Ludum Dare #18, and I didn’t feel it was worth releasing.

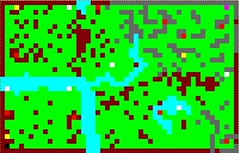

My second project was my LD #18 project, Stop That Hero!, which involved the most complex AI I’ve ever implemented. That is, I’ve never implemented pathfinding algorithms more complex than “go directly from point A to point B”, and in The Old Man and the Monkey Thief, I learned that there was a lot of problems with a character that couldn’t avoid obstacles well. Stop That Hero! took me three days to finish, but I was fairly pleased with how it turned out and wanted to flesh it out later.

I never did make a third project.

Still, two finished games in a month taught me a lot, and I was getting feedback from friends and colleagues. Even though I failed my August goal of making three games, I made good progress towards it and learned plenty.

Unfortunately, September started without goals set for it. In order to figure out what my goals should be, I spent a good chunk of the first week or so figuring out my options as an indie game developer. I thought it would take me a night to write down the options, but then I thought I could write up an article or two for ASPects, the Association of Software Professionals newsletter. It ended up being four full length articles, and it took me almost the entire month before I submitted all of them. If you’d like to read the articles, for now the only place they’re available is in the ASP members-only archives.

I also caught up on some reading. Business articles, audiobooks, and other literature were consumed. I would highly encourage anyone starting a business to read The E-Myth Revisited . For a long time I ignored it because I thought the E- part of the name meant it was a book about how Internet-based companies aren’t get-rich-quick schemes. I didn’t know it was a book about why most small businesses fail and what you can do to succeed.

. For a long time I ignored it because I thought the E- part of the name meant it was a book about how Internet-based companies aren’t get-rich-quick schemes. I didn’t know it was a book about why most small businesses fail and what you can do to succeed.

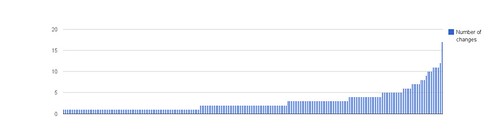

Anyway, I spent the latter half of September analyzing the heck out of Stop That Hero! and trying to figure out what design directions to take it in. This time coincided with the creation of an organized daily schedule. It gave me some much needed structure, and I felt much more productive and focused, and I didn’t feel like I was letting anything fall through the cracks. I had time for writing, reading, organizing, and most importantly, game developing.

The October Challenge

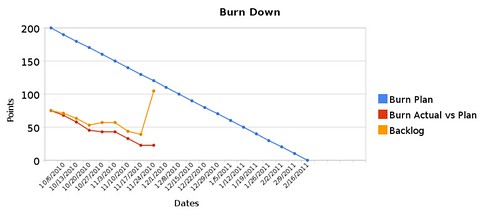

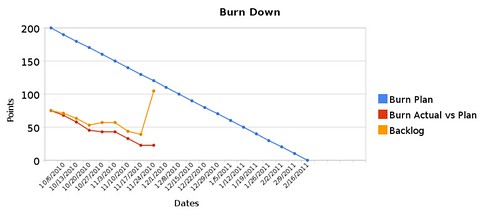

While I wanted to flesh out and sell Stop That Hero!, I was having difficulty figuring out out how long to allow the project to run. I didn’t want to put together a skimpy game in a matter of weeks. Who would pay for it? And I didn’t want to spend six months working on it since that would be half of my burn rate. I don’t want to spend all of my savings on one game, and I don’t want to put together disposable games. I learned that Flashbang Studios used 8-week projects, but they had entire teams working on their games. Did I need longer? Could I afford to take longer?

Then Mike Kasprzak announced the Ludum Dare October Challenge, and I had my deadline. Make a game and sell it by the end of the month? I could do that! It took me only three days to make the prototype, so a full month should be plenty of time to make Stop That Hero! with multiple campaigns and different game modes. Right?

I wrote an October Challenge post-mortem, but suffice it to say that I didn’t get the game finished in time. Read the post-mortem for more details about what went right and what went wrong, but one of the biggest problems was not realizing how much technology I didn’t have to leverage.

Hacking a dinky game together virtually from scratch in a weekend is one thing, but making a full-scale game requires a lot of infrastructure and technology that I didn’t have. Rather than go without, I did research and development, which took up a lot of time. Tracking entities and game objects in a way that didn’t require a ton of dependencies was surprisingly difficult, and I wrote about my difficulties in implementing a component-based system in State of the Art Game Objects.

Of course, developing infrastructure is not developing the game. It’s just laying down the groundwork for a game. Kasprzak took time off to work on a framework after PuffBOMB HD, but it sounds like a lot of it was already in a game and he was cleaning it up and improving on it. While I had some prototype code, a lot of it needed to be reimplemented. Stop That Hero!‘s pathfinding algorithm was fairly hacked together, leaked memory like crazy, and required a few other algorithms to compensate for when it wouldn’t work well on its own. The new version is less dependent on knowledge of the entities moving through it and works very well, but it took me way longer to write than I would have liked.

Besides creating the necessary technology for the game, I’ve never worked on such a large scale before. Programming is not software engineering and hacking is not project management. I didn’t have much experience leading or creating a serious project before this one, and I found myself struggling with choices. What do I call this class? Should this be its own class in the first place? Is this overengineering or good practice? And that’s just the software architecture. There was also the question of project scope. I was behind schedule, and it wasn’t due to feature creep. What was I doing wrong?

Continuing the March Towards Completion

But if I could get the game done by Christmas, I think I’d still be doing well. The October Challenge was just a fun deadline and wasn’t a must-hit, urgent business deadline. According to the work I have identified and my actual rate of work, I thought I had a more accurate project estimate, and Christmas seemed to be a doable deadline. From what I’ve been told, there is a trend of increased sales around Christmas, so it might work out better for me. I pushed forward.

I was making decent progress at first, but the end of the month involved Thanksgiving and moving out of my apartment. To make matters worse, individual game systems weren’t working quite right, so I spent part of the last week finding and fixing bugs for work I thought was finished. I was finally hitting my weekly estimates, but there were also setbacks. Progress was still slower than I would have liked overall.

Unfortunately, near the end of November, I saw my schedule slip even more when I identified a ton more work. When hacking a prototype together, there can be missing menus, level selectors, data permanence, or any number of other aspects of a game. A full game missing these features isn’t a full game, by and large. When I initially planned out the project, I glossed over a lot of these kinds of details. I wanted multiple game modes, but I didn’t plan for them, nor did I figure out how I wanted the player to access them. Suddenly my project ballooned to almost twice its size, with a likely deadline in February or March, which made Stop That Hero! the six month project I wouldn’t have started if I knew.

The Future!

It was demoralizing to miss the October Challenge deadline, but this new estimated deadline was frustrating. I initially hoped to make my first sale at the end of October, and now I might not do so until after winter? And that’s assuming anyone is interested in buying it in the first place!

All this time, my savings account has been slowly reducing in size, and it will continue to do so. I’m well aware that I don’t make money producing a game. I can only make money selling a game. I could shelve Stop That Hero! temporarily while I work on something smaller, but I fear I’ll simply end up in the same situation writ small. That is, a smaller game still requires a lot of technology and infrastructure that I don’t currently have. Plus, I don’t like the idea of dropping a project midway and starting a new one. I’m tired of unfinished projects on my résumé.

I read a lot of things that get me second-guessing my choices. Is Stop That Hero! too complex and hard to make? Should I focus on “evergreen” mechanics, as suggested at Lost Garden? Is TDD inappropriate for getting games finished quickly, or is it necessary for getting games finished quickly? Am I expecting too much from my first project, or should I take the problems I’ve encountered as a sign? Am I running into the same kind of problems everyone runs into, or do I need to scale down my ambition until I have more experience? Do I need to work on smaller projects to build up my technology and code base, or can I continue building what I need when I need it for this project? And before you ask, yes, I have made a Pong clone, among other simple games, so it isn’t like I was jumping into a very large project without any experience at all. Or, maybe the problem actually is that I don’t have enough of these simple games under my belt.

There’s a lot of uncertainty, and it would be easy to panic or freak out (and I have at certain points!), but it is good to have some perspective. In six months, I’ve done more and learned more than I have in the last five years prior. While I expected to learn a lot during this time, my existing knowledge wasn’t as helpful as I thought it was. I’m taking on roles that I never had experience with before. Before I went full-time indie, I didn’t make decisions that would have a major impact on my business, and it’s an enormous responsibility.

And yet it isn’t a crippling responsibility. It’s exhilarating!

While I have the added burden of figuring out what specifically is important, I get to focus on it as much or as little as I want. While it’s a little scary to think that my decisions can make or break my business, they’re my decisions, and part of the fun of running your own business is in learning how to make better ones. The stakes are high, but at least I’m not settling for less out of a need for security.

Six months ago, I had very little idea that I’d make the progress I have and face the challenges I did. I knew it wouldn’t be a cake walk, but I also knew it wasn’t impossible. If I could change anything, I’d have tried harder to produce results while working part-time. I wish I had more direct experience working closely with other people making games so I didn’t have to figure out nearly as much on my own.

Still, I’m only six months out, and I’m in it for the long haul. In 2015, I hope I’m writing my own five year retrospective with plenty of good news to report.

If you are a veteran game developer, do you have any specific wisdom to share or regrets to warn against? If you are an aspiring game developer, do you have any questions about what the future might hold? Please post them below!