Note: this post was originally published in the March 2014 issue of ASPects, the official newsletter of the Association of Software Professionals.

Many people have tried to create a comprehensive definition of games but have failed. Most definitions are either insufficient in that certain games are left out, or they are too broad and encompass too much that are not games. In “Designing Games”, Tynan Sylvester writes that games are “an artificial system for generating experiences.” Disney amusement park rides are clearly not games but would be considered such by this definition. It’s obvious he erred with the latter option.

Still, Sylvester’s definition is useful when approaching game design from the point of view of the player. When you tweak a space marine’s jumping ability, what emotion are you trying to provoke? When you insist on having simulated people visible in your simulated city, what is it that you want the player to think? How did the designers change the player experience in Super Mario World by ending levels with a giant gate instead of the flagpole from the original Super Mario Bros?

Much like the principle of Chekov’s Gun says that everything seen or mentioned in a film, play, or story should serve a purpose and everything else should be removed, game design demands that you make decisions in the same way. According to Sylvester, games are made to provoke emotion. As he puts it, “think of a game as a strange kind of machine – an engine of experience.”

The first part of the book is about the nature of games. The author identifies mechanics as the basic rules that define a game, then identifies the interaction of mechanics and play to generate events. A mechanic might be that a player can run. An event is what actually happens, that is, the actual running a player is doing. While most other entertainment media author events directly, events in games occur at the intersection of rules and play.

The key to being a good designer of games is to engineer mechanics that result in meaningful play. Events should be important to the player. He makes the claim that the importance of an event comes from the emotion it provokes. While emotions don’t have to be extreme, they matter. A key skill is identifying subtle emotions.

Sylvester argues that events have emotional relevance when they change the states of values that are important to people. In the game Minecraft, players are attacked at night by creatures, putting them in a state of danger. It is only in building a fortification that a player feels safety. In Lemonade Stand, selling lemonade means a shift from poverty to wealth. In World of Warcraft, joining a guild to fight a major enemy turns strangers into friends.

The greater the emotion, the more significant an event can be. Selling one extra cup of lemonade on a hot day might merely result in a few more cents in your pocket, but selling one extra cup when it means the difference between profit and loss is a huge victory. Some games give you bonuses for doing an event multiple times in a row. For instance, after Pac-Man eats a power pellet, the ghosts turn blue for period of time, and they are edible. Eating a ghost in Pac-Man gives you 200 points, but eating a second ghost gives you 400, a third 800, and a fourth 1600. The event is the same, but each subsequent event has more riding on it.

It’s the combinations of emotions along with the thoughts and decisions of a player that makes up the experience of play. The second part of the book is about how to create a game to generate the general experience you desire for players, the craft of game design. The chapter on elegance focuses on how to create emergent complexity from a few mechanics. Another chapter focuses on skill and how it creates barriers to entry to a game as well as dictate how deep a game is. Tic-Tac-Toe is a solved game for grown-ups while young children might find it a challenge. Chess, on the other hand, seems to have a skill ceiling that is beyond our abilities to master completely. In between we have games that are fascinating until players become bored with them.

The chapter on narrative focuses not on how to craft a good story but on the tools one may use to do so in this interactive medium. A fantastic concept is the idea of apophenia, which is our tendency to see patterns in complex data. I’ve heard of game designers amazed that players attribute malice and tenacity to an enemy that is in actuality programmed to act randomly. Apophenia means that emergent stories can come out of games so long as enough information is there to give players a reason to think. Out of the techniques the author mentions for generating apophenia, my favorite is labeling. Giving two identical monsters the names Poindexter and Grunt might result in a player thinking that one is acting much more intelligently than the other, even if it isn’t the case. There’s also the implied backstory regarding how those creatures were given those names. Labeling can also apply to attributes as well. It’s similar to writing a novel and describing a character as ravishingly gorgeous. Rather than actually write details about how someone is attractive that may or may not appeal to a reader, the reader’s imagination fills in the blanks, resulting in a richer and more entertaining story even though you actually provided less.

There are also chapters on decisions, balance, multiplayer design, motivation and fulfillment, and a game’s interface. I really appreciated the chapter on the market. “Every design decision is affected by the purpose the game was created to serve”, whether it is getting someone to buy a commercial game or walk away with deep thoughts after playing an art game. The entire chapter is about understanding the market you are creating a game for, and it is one of the biggest gaps in most books in game design. I’m pleased it was addressed quite well in this book, providing tools such as positioning and value curves, and explaining market segments, while also reminding the reader that models are imperfect.

For example, no one could predict that StarCraft would become a cultural phenomenon in South Korea. It was the result of a confluence of the popularity of Internet cafes, recent investments in broadband infrastructure, a recession that provided incentive for inexpensive entertainment, and TV channels dedicated to the boardgame Go that made broadcasting professional StarCraft matches a logical conclusion. Another example is The Sims, the greatest selling PC game of all time. It created its own market after struggling to get buy-in from the publisher. Existing models gave no indication that a video game about playing house would be so popular.

The third part of the book focuses on the process. Game design is geared towards the creation of a game, which is a major project. Planning such a project is much like planning a software project: sometimes we don’t know what we want until we see it working, or not working, in front of us. Playtesting is needed when tweaking mechanics or introducing and removing others entirely because it is only through play that a designer can understand the experiences being generated by the changes. Planning becomes difficult as a result, but planning can’t be ignored.

Iteration is the key, and Sylvester borrows ideas from Eric Ries’ “The Lean Startup”. We have uncertainty at every step in designing a game, so we conduct experiments to resolve the uncertainty. The steps are to plan, build, and test, and you do so to get back information about what works, what causes confusion, what problems might exist, and more. The book explains how to conduct playtesting, and it dedicates another chapter to ways to generate the designs to test in the first place.

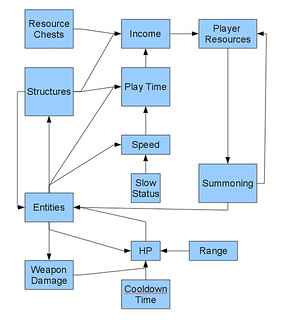

I learned quite a bit from the chapter on dependencies, an understanding of which can help mitigate the risk that comes with creating a game. By identifying how various aspects of a game design are interrelated and dependent, we can create a graph called a dependency stack. The dependency stack informs us what aspects of a design to focus on implementing first. If goblin raids only make sense if there are castles to raid, you want to focus on the castle-building aspects of the design first. What’s more, a change in the implementation of castle-building would likely cascade to changing how goblin raids work, so a dependency stack also provides information about the risks associated with change. The biggest benefit it can provide is helping the designer identify the core game play, the minimum mechanics at the bottom of the stack that provide the meaning and experience desired.

There are some sections on management, teamwork, workplace politics, and handling incentives to work on a project. While these are all covered quite well in entire books on their own, Sylvester touches on them as a warning to aspiring game developers: recognize that game development is hard.

There’s a way to make it less difficult though. The last chapter focuses on the importance of the values that a game designer has. “I don’t think anyone can prescribe the best values for all designers. I do, however, think that every designer could benefit from thinking about what values they believe in. Because values keep us steady. They are immutable standards that stabilize us against the political and emotional turmoil of daily design work.”

Between this chapter and the one on understanding the market, Sylvester demonstrates his understanding that games don’t get designed in a vacuum. Too many game developers throw something together and put it out without any thought to why. The recent news about Flappy Bird’s creator taking down the highly profitable app because it brought him too much attention highlights the importance of knowing what you are getting yourself into when designing a game.

While I found some of the concepts in the book have been mentioned elsewhere, such as Jesse Schell’s “The Art of Game Design”, and I wish Sylvester would have touched on concepts such as the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) model, I would highly recommend “Designing Games” for its comprehensive treatment of game design. I know I have quite a few new tools I want to wield at my own projects.