At the end of the last progress update, I mentioned the realization that there could be a lot of code and logic in the player-facing parts of the game that aren’t part of the game. That is, when people talk about how complex the interface can be, they aren’t talking about particle physics, 3D culling, or fancy special effects. They’re talking about how the front end’s complexity can rival the back end’s.

And somehow I hadn’t realized it before. I knew that the interface should be separate from the game, but I didn’t know that the interface was responsible for more than merely displaying the game world and its objects. It’s a heavy-weight in its own right, handling menus, HUDs, and inputs that the simulation ultimately doesn’t even know is happening.

I used StarCraft‘s interface to illustrate the idea that the player interface is more than a mere window into the simulation. It can have complex logic that the game simulation doesn’t actually care about. As far as the simulation is concerned, it receives commands. Most of the actions you take in StarCraft do not result in commands to the simulation.

If you click on an SCV, and then click the Repair button, and then click a burning Bunker, the interface is responsible for figuring out what you’re trying to do. It isn’t until you click on that Bunker that the simulation receives a command along the lines of “SCV 1 REPAIR BUNKER 5”. Up until then, only the interface has to know you’re working with a particular SCV, what commands are available to an SCV in general, what buttons to display in the SCV menu, which SCV menu you’re looking at, etc.

Stop That Hero!’s interface

Now that I know that I can expect the interface to my game to be incredibly complex as opposed to a dumb and simple view, it actually made it much easier to realize how to proceed with my project. I don’t have to do everything within the simulation, and in fact, I can expect a huge part of the work to involve the player’s interface.

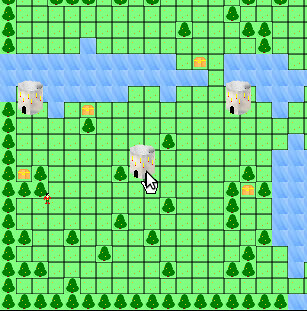

Stop That Hero!‘s interface isn’t like most games in that there is no avatar to control. You’re not directly moving an entity with the arrow keys or commanding it to jump with the spacebar. You simply create them at the appropriate towers in the world, and they’ll figure out where to go and what to do on their own.

But how do you create them at towers? The original prototype had a menu hardcoded at the top right of the screen. If you wanted to create a monster at a tower, you had to click the monster icon at the top right, then click on the tower. If you had enough resources, you summoned the monster you selected.

It was functional, but I didn’t like how it felt. Why is the selection of the monster to summon separate from the act of summoning? While it makes it easy to create a bunch of the same type of monster at once, it’s also easy to accidentally create a monster if you click on a tower without wanting to.

I wanted something more intuitive, and it turned out that pie menus are exactly what I want.

Except my GUI code is incredibly basic. I have menu screens and buttons, and everything assumes it is starting at the top left corner of the screen. In order to even simulate a pie menu, I needed a way to display menus at arbitrary locations, and it would help to be able to offset a menu from its center instead of the top left corner.

Which meant giving menus dimensions (how else can you know what the center is?) and having my IMGUI-ish system understand how to display and detect updates at arbitrary offsets.

In the end, after some research, questions, and determination, I do have this sequence working:

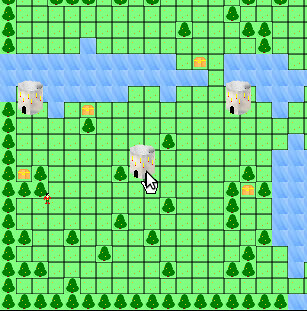

First, click on the tower you want to summon a monster at:

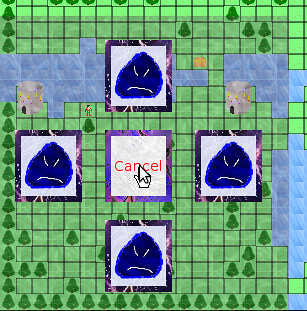

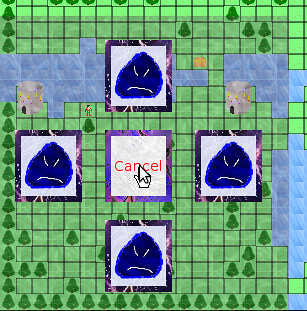

The Monster Summoning Menu appears over that tower, which means it is right under your mouse cursor:

Select the monster you want to summon by moving your mouse cursor to the appropriate icon. Right now, I only have a Slime, but others will be added later:

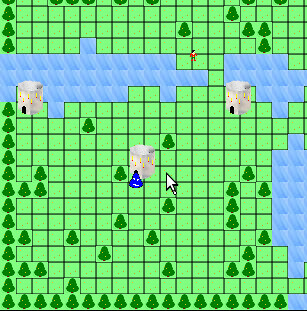

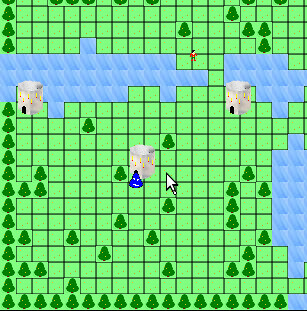

Congratulations! You’ve summoned a Slime monster!

Besides the infrastructure changes to support arbitrary menu placement, configuring the menu is easy, and each button fires off whatever event I want when it is clicked.

Tricky Aspects

One of the things I still need to figure out is what to do with a tower near the edges of the screen. Right now, the menu is always centered on a tower, which means clicking on a tower near the side of the map results in a menu with icons you can’t see. They’re being displayed off screen.

It’s not such a problem if I can display the menu outside of the screen the way a game like SimCity/Micropolis does, but since I’m not using Gtk to render the menus, they have to be rendered within the screen. I could add more screen real estate around the play area, but I’m trying to keep the game at a low resolution like 800×600 to accommodate players with older computers and netbooks. I could make the play area scroll, so even if you were at a corner of the map, it would be displayed in the center of the screen, but I want the players to see everything at once. I could reduce the play area so that I have a border to work with, but I’m not sure I like losing so much level data just because of the UI.

My best option if I want to keep the pie menu is to detect if the menu is being displayed offscreen and have it adjust automatically, but I’m not sure if the menu appearing away from where you expected it becomes too unintuitive, defeating the purpose. Otherwise, I might have to get rid of the pie menu altogether.

RTS development in a vacuum

In any case, I now have a player interface that I can easily change, but one thing I didn’t anticipate was how similar it is to a real-time strategy game’s interface. I didn’t really think of Stop That Hero! as an RTS, and yet I suppose Dungeon Keeper and Populous had RTS-like interfaces, too. Or, rather, the interface is composed of icons that let you influence the world.

I discovered that while FPS or platformer development articles and tips are a dime a dozen, RTS development seems to be something that everyone must reinvent themselves since there is a lack of information out there. I know of a couple of strategy game programming books that focus on DirectX, and either people found them lacking, or they focused heavily on DirectX as opposed to the game.

Even if there was a basic breakdown of every aspect of an RTS project, leaving the research of each item as an exercise for the reader, I’d find it more helpful than figuring out what those aspects might be as I stumble across them myself.

While most games probably have a hard-coded GUI baked into a game, some games are more expandable upon release. I remembered that Total Annihilation allows player-created units, and I figured that there had to be a way to provide access to the GUI so that new units can be created by the player in game. I checked out the game’s modding tools and discovered how it handled its GUI elements. I spent an entire day perusing technical references and modding tutorials, peaking at the game’s default data files, and generally immersing myself in the internals of the game. It is fascinating how GUI images are tied loosely with the name of the unit or command.

World of Warcraft isn’t an RTS, but its GUI is supposed to be highly configurable by players, and there are interesting references explaining how the XML ties in with Lua commands and functions within the game.

Looking at how other games do it with the limited access they provide is like trying to study a map by staring at the back side. It’s hard work, and I’m sometimes limited by the games I have access to for the most part, but it is sometimes the best guidance I can get when it comes to figuring out how to implement my own game.