Related to the fact that I’m having slow project progress on Stop That Hero!, I wanted to expand upon this thought:

I’m using Test-Driven Development on this new version of the game to ensure that bug fixes and game updates are as easy as possible. If a paying customer finds a bug or if I release a new feature, I want to make sure that new code works and that old code doesn’t break.

I also wanted to discuss over-engineering.

Estimated Project Progress

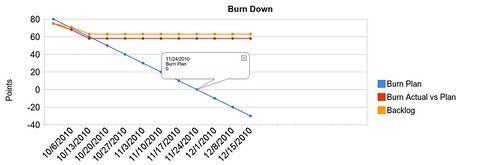

This chart shows my estimated burn down if I was working at the ideal rate of 20 story points per week, assuming my project doesn’t exceed 80 story points.

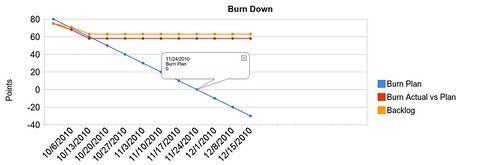

In the last two iterations, I’ve found that I’ve only accomplished 7 and 10 points. Assuming I can continue at 10 points per week, here’s my updated chart:

It might be a bit hard to tell since Google Docs don’t give me much ability to change the axis in these charts, but in the first case, I am well on my way to hitting the October 31st date. In the second case, this project won’t be finished until the end of November.

With Thanksgiving coming and plans to move out of my apartment, November isn’t an ideal development month either, so it’s more likely that it will be December before the game is finished. And what about playtesting and game balancing?

Yeesh. Well, the solution is simple, isn’t it? I just need to do 20 points worth of work each week. Quit being so lazy, Self!

In all seriousness, though, the 20 points was an estimate of the points I could complete each iteration, and that estimate wasn’t based on hard data yet. Two weeks later, armed with some data, I was able to generate a few charts such as the ones above and analyze them.

My Analysis

My original estimates didn’t take into account how much time I’d spend getting the basic infrastructure of the game under test. More importantly, I didn’t specify how data-driven this game would be at the outset.

The more data-driven the game is, the easier it is to modify, configure, and improve. I read that a game such as Age of Empires literally used a database to specify each entity in the game. It allowed designers to modify the database values for various units and see those changes in the game quickly.

The original Stop That Hero! is almost completely code-based. The only data loaded is the level layout, and out of all of the things I could tweak in the game, that level layout was the easiest to change. The level was loaded based on this image file, which is blown up to make it easier to see:

I could update that image in an art program, then see the update the next time I ran the game. It would have been even faster if I could reload the file on the fly instead of having to restart the game. Still, the point was that it was easy to change the terrain and the location of towers and treasure chests without recompiling the game first.

But what about the enemies in the game? They are all implemented as instances of the same class. In fact, the Hero is just another instance of that class. Couldn’t they be loaded from a file, too? Sure! I could load a file that specifies what sprite to use, the dimensions of the monster, the speed, the strength, and a number of other attributes. If I had done so, I’m sure balancing at the end of the Ludum Dare Jam would have been easier and more effective.

Variables such as enemy stats, resource costs, and chest contents are great to put in configuration files and scripts, but how far do you take it?

Ideally, even game logic could be loaded at run-time. Instead of hard-coding that you win when the Hero has no more lives left, why not make it a specific instance of a Victory Condition? This way, I could create other Victory Conditions for different kinds of game modes. I could make a tutorial level where the Victory Condition involves creating one of each type of monster, for instance.

And speaking of levels, the original game only had one. How do I create multiple levels? I’d have to create some kind of level collection or campaign, and each level might have its own Victory Conditions. And if I’m going to be able to do so much configurable work, I might as well let the players come up with their own mods, too! I wonder how quickly someone would make a Tower Defense game out of Stop That Hero!…

Yes, the more data-driven the game is, the more interesting it could be. Bug fixes, patches, expansion packs, and feature updates can be as simple as adding or changing data, and if code is needed, it should be relatively simple to write.

The thing is, to get to such an ideal data-driven game in the future, I’d have to do a lot of work NOW. Maybe later balancing and game play tweaks and entire rule changes can be easy to implement, but for now, I’d need to lay down a lot of infrastructure.

Infrastructure and Over-engineering

The biggest source of stress for me is the oscillation between wanting to implement just enough of the game to sell a complete copy by October 31st and wanting to implement a game that I can easily update.

Again, October 31st isn’t a hard deadline for my business. It’s a deadline for an inspiring challenge, but missing that deadline isn’t the end of the world. Besides, once the game is finished, there’s still a lot of work to do. Customer support and maintenance are my chief concerns.

If I really want to hit the challenge deadline, I probably can’t make the game very configurable or provide multiple game modes. Still, if it means having a finished game out and selling sooner, maybe lassoing in the scope is a good thing. After all, I could always update the game later with new features, and I can even have the benefit of customer feedback. “Release early, release often.”

On the other hand, I might implement the game in a way that is hard to change. After a weekend of Ludum Dare, I have a rigid, hard-to-change game. If I make this new release fairly rigid as well, what happens when customers complain about bugs? How hard will it be to fix them? I could always add features later, but how much more effort would it require if the code isn’t set up to make it easy?

By taking my time, I could end up with a much better game. It can be slow-baked to perfection instead of being rushed out. It would be easier to configure and mod, and I believe it would result in a much better value proposition for the customer.

Of course, it’s all speculation. It could be that I’m putting in all this effort and over-engineering the implementation for nothing. While it is good to think long-term, what if I don’t need to do everything now? I could forget about creating configurable Victory Conditions and other rules for the moment. If I focus on loading variables from files while assuming that the rules are still the same, I could go a long way.

I think you could only say that something is over-engineered if it anticipated future needs before they became real needs. In this sense, making the game configurable is a real need, and so writing the code to allow it wouldn’t be over-engineering.

But I’d have to make such a need explicit, and I don’t believe I had at the start of the project. Oddly, I felt torn between two different assumptions: I’m releasing at the end of October with as good of a game as I could make by then, and I’m releasing the game only when it full-featured and highly polished. My anxiousness about wanting to develop just enough to release something soon versus wanting to make something with more value was because I hadn’t spent much time on project specifications.

It sounds more formal than it is. Basically, I haven’t decided on exactly what game I’m making, and I was hoping to offload that work to the configurable nature of the engine I’m writing. I wanted to make the game so easy to modify and change that I can experiment quickly and see what works best. While it can ultimately work out really well, it’s a recipe for taking as much time as I am allowed. Of course, I work for myself, so no one is there to hold me to a deadline but me.

A concern is that until I start earning income from paying customers, I’m relying on my savings to live and work. I can’t afford to spend 3 years on a single game, but even spending six months in development would translate into losing a huge chunk of my savings. It’s too risky. On the other hand, I don’t want to try to churn out lots of games in mere days or weeks. I can’t see making anything worth being paid for in that time frame, and spending months releasing poor work isn’t a good use of my time, either.

In the case of Stop That Hero!, releasing it sooner, even with fewer features, is better than spending forever trying to make it perfect. I can always make it perfect with the benefit of customer feedback, and earning any potential income sooner rather than later is a nice bonus, too. B-)