Gregg Seelhoff announced that he attended Meaningful Play 2008, an academic conference ” that explores the potential of games to entertain, inform, educate, and persuade in meaningful ways”, and he posted his notes.

- Day 1: Want some good data on casual gamers and Flash game business models?

- Day 2: Want some good data on 60+ year-old gamers as well as serious games?

- Day 3: The wrap up, with some information about a panel on board games.

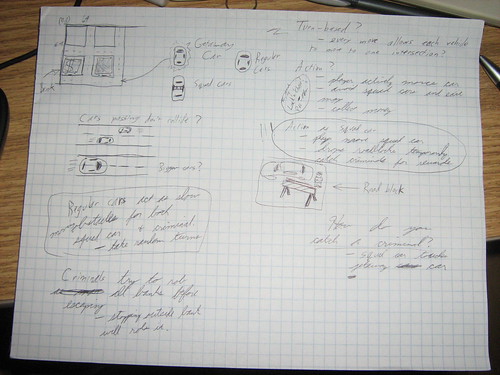

I’ve been thinking about the kind of games I wanted to make, and rather than create short-term sales product that will be thrown away within a week, I’d like to make games that matter. Games that stick around long after you’ve played them, like a good book or a good movie. I really liked the idea of an entire conference dedicated to meaningful play, and I hope I can attend the next one. There were some good nuggets of information that Gregg managed to report, such as who plays games at Pogo.com and for how long, but I especially liked reading the following on what kinds of serious games received good reviews:

An acceptable game (threshold 1) succeeded in the areas of technical capacity and game design. A good game (threshold 2) passed threshold 1 and, additionally, succeeded with aesthetics, visual and acoustic. For a game to be great (threshold 3), it had to pass both previous thresholds and also succeed in the final two areas of social experience and storyline (“narrativity and character development” is too long). Few games reached the final threshold.

Look at that! A prioritized list of what makes up a good game!

It’s unfortunate when you can’t play games because they are made for specific platforms, especially when there is always this emphasis on the ubiquity of Flash. Many of the games Gregg links to were Windows-specific, and they wouldn’t run in Wine. When so many of these games aren’t even meant to be commercially viable, is it still a valid argument that providing a port to other platforms such as Mac and Gnu/Linux would be pointless since having access to a few hundred thousand more players wouldn’t be worth it?

I would have liked to know more about Ian Bogost’s keynote, but Gregg provided some good notes for most of the rest of the conference. I have more than a few PDFs to download and read through.

[tags] meaningful play, game design, game development, serious games, casual games, conference [/tags]