A few weeks ago, I started working on a new set of updates for my leaf-raking business simulation Toytles: Leaf Raking, originally released in 2016.

I wanted to focus on making the neighborhood come to life by giving it some personality and character. I plan to do so by allowing your neighbors to talk about story lines happening in their lives.

My current project plan is in a spreadsheet I manage through LibreOffice, and with the COVID-19 pandemic, it took me quite a few months before I could focus on it. It mostly came together in June.

The original plan was broken down into weekly sprints, and I decided to continue to do so despite not having nearly as much capacity to get much done in a given sprint. Still, having a plan did wonders for my productivity.

What follows is a quick report on how the last few weeks have been.

Sprint 1: Start of personality injection

The first sprint was from June 21st to June 27th, and I wanted to get a few things done:

- Give player option to accept a client when visiting a neighbor

- Update copyright date on title screen

- Chat w/ Mr. Matt at General Store

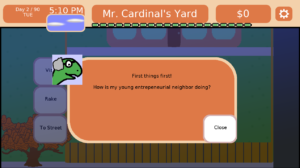

- Give each neighbor unique chat text

Before that sprint, visiting a neighbor was the same as asking for work. Effectively, it meant you never visited anyone because you didn’t want to take on too many clients, which meant most of the neighborhood was pointless. This change should open up the way towards future work which will allow the neighbors to have more personality and give the player a reason to chat with them that doesn’t involve cold calling them for business.

I wanted to add the ability to talk to the store owner for the same reason. He doesn’t even exist in the game except for his name being on the store, and I want to make him a living, breathing character, too.

I wanted to update the copyright date to make it dynamic instead of baked into the title screen art, which should make it easier to update in the future. It was a fairly straightforward change.

And once you can visit a neighbor without asking for work, I wanted the ability to hear each neighbor say something unique when you call upon them. This change should mean that the neighbors are no longer essentially interchangeable numbers in a simulation, even if it is only one piece of dialog.

For that sprint, I did 2.5 hours of game development. It may not sound like much, but…well, it isn’t much. But again, we’re in a pandemic, I have kids, and there was some turmoil at my day job, so all in all, I think 2.5 hours sounds like plenty. Well, not really. I still worry when I don’t get much done in any given week, lamenting that if I was focused full time on it that I could probably get it all done in a day, but I’m trying not to dwell on it.

Unfortunately, I only got the copyright update and the visit option done.

Sprint 2: Start of personality injection (continued)

It took the next sprint to get the other two pieces of work accomplished, and that took me 7.75 hours of work, which included putting together the v1.4.0 release for both Android and iOS.

Sprint 3: Start of personality injection (continued)

Ok, so my first update to Toytles: Leaf Raking has introduced the tiniest amount of personality to the neighbors. To build upon it, last week’s sprint from July 5th to July 11th focused on writing more dialog:

- Give each neighbor unique text as clients

- Give each neighbor unique text as ex-clients

There are 19 neighbors currently in the game. The v1.4.0 release has the neighbors say something unique, and now I wanted them to say one thing as a prospective client, one thing as a client, and one thing if they become an ex-client.

For example, Mrs. Smith is a sweet neighbor who loves it when you visit, so she says, “It’s always a pleasure to see you.”

Once she hires you, she says, “I’m so proud of you. It’s a joy to see you work hard. I’m sure you’ll go far in life.”

And if she has to fire you for doing a poor job of raking her leaves, she says, “Well, not everything works out. I’m sure you’ll bounce back.”

Not all the neighbors are so nice.

Last week I did 3.75 hours of game development, finishing the sprint very late on Saturday night. Considering I also spent 2 hours writing a blog post and a newsletter mailing to announce the published update from earlier in the week, I felt like I did well to make time for the project, all things considered.

I also gained a greater appreciation for the work of game writers.

Sprint 4: More personality injections

Which brings me to this week’s sprint:

- Give each neighbor unique text as unhappy clients

- Add variation to weekend flavor text

Currently, if a client is not happy with you, you will learn about it in the morning from your mother. She will inform you which clients are worried that their lawns are not being taken care of, often when over half of the lawn is covered in leaves.

But if you talk to those clients, they will continue to say the same thing they said before. Giving them something to say when they are still clients but are also concerned about your work is once again adding a little more personality and character into the game. Eventually I’d like to get to the point where the way they say something is impacted by your reputation with them, the weather, and possibly anything that is happening in their lives unrelated to your work.

Another area of the game that could use some variety is the weekend text. On weekdays, you wake up, go to school, and then come home to start your day. On weekends, however, you currently get to hear about one of two dreams you have. I want to add at least one more weekend dialog for each week.

Eventually that weekend dialog should have random events, such as a neighbor willing to pay double for getting to their lawn that day, or perhaps you learn that a client has a nephew in town who raked their leaves for them so you aren’t needed that day. But that kind of feature will be for a future update.

Until next sprint

I hope you enjoyed this behind-the-scenes report of my progress on Toytles: Leaf Raking’s Personality Injection updates. I plan to provide a weekly report going forward.

While I would love to have a huge big bang update to release with a ton of changes, I will instead be working slowly but surely, adding a little character each time. Eventually, the game will feel completely different, but I will get there one step at a time.

—

Want to learn when I release updates to Toytles: Leaf Raking or about future games I am creating? Sign up for the GBGames Curiosities newsletter, and get the 24-page, full color PDF of the Toytles: Leaf Raking Player’s Guide for free!