In the Game Design Concepts course, I’ve found that one of the most beneficial aspects is the amount of practice with creating prototypes. Since the class is about video game design, there is a bias that any prototypes would also have to be in software, but the instructor is adamant that computers aren’t needed.

Just taking a few minutes to do a quick assignment or two, it is easy to demonstrate for yourself how useful paper prototypes can be. Right away, you can tell if the mechanics you’ve put together are dead in the water or if you have a good chance of creating a game other people would want to play. On the first day of class, for example, there was an assignment to quickly create a race-to-the-end board game. The steps seemed easy enough:

- Draw a path and separate it into spaces.

- Create a theme.

- Create the rules that dictate how the players move.

- Create ways to interact with your opponent.

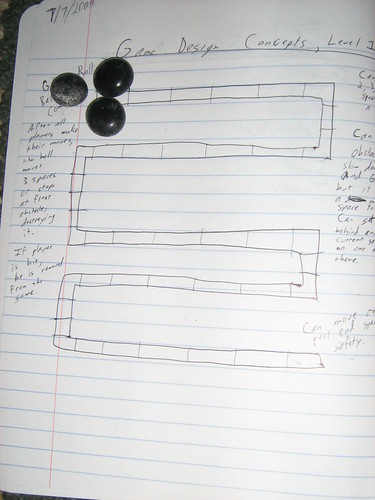

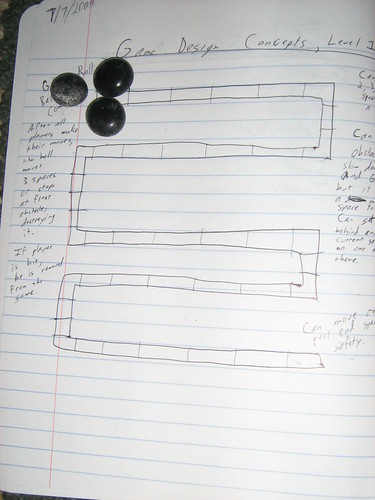

Here’s the prototype I created on my first pass:

The path winds down the page, although effectively it acts the same as a straight path. That’s Step 1.

Step 2, I decided that the two players are racing to the end to avoid a giant rolling boulder that is following them. I used some pebbles I have in a bowl on my coffee table to act as the players, and I picked a dirty one to be the boulder.

Steps 3 and 4 were interesting. The easy choice would have been to use dice to determine how far a player moves on a given turn, but I didn’t want chance to be involved in the game. I wanted the players to make interesting choices instead. I decided that the players could move 2, 3, or 4 spaces on a turn. If they move less than 4 spaces, however, they can instead place an obstacle behind them for each space they don’t move. That is, a person moving 4 spaces can place no obstacles, a person moving 3 spaces can place 1 obstacle, and a person moving 2 spaces can place 2.

After both players finishes their turns, it’s the boulder’s turn. The boulder will move 3 spaces, but it will stop early if it hits an obstacle. The obstacle is destroyed in the process of stopping the boulder.

The obstacles can be used to slow down your opponent as well. So if you move ahead and hit an obstacle, you destroy it, but have to stop moving forward to do so.

If the player is hit by the boulder, he/she is removed from the game, and the other player wins by default.

Great! That sounds cool. What’s next?

Well, let’s play it!

…

Ugh. This game sucks and is riddled with horribleness! What I found right away was a problem with one of the rules. If you can drop multiple obstacles…where do you put them? There is only one space behind you, so you can’t place both of them there. So does that mean you can place one behind you AND on the space you’re currently on? Sure…

But that leads us to the fundamental problem with the game. Whoever goes first, wins. The first player can move ahead and drop an obstacle. The second player will move and hit that obstacle, being behind the first player. Then the boulder moves forward and crushes the second player.

So I tried tweaking the rules of movement. Maybe you can only move 3 or 4 spaces, and if you move 3 spaces, you are allowed to drop one obstacle. Maybe the boulder can only move 2 spaces. Unfortunately, these small tweaks still had the fundamental problem. I realized that if I wanted to avoid randomness, I would need to do some bigger changes to make this game work. Perhaps change the level layout so that the players can choose where to move instead of always moving along a straight line? Maybe obstacles can only be moved around and not created?

Regardless of what gets decided, the point is that playing the paper prototype, which took mere minutes to create, made a major flaw obvious. Imagine if you were going to spend time writing code, creating art, and producing sound effects and music for this game, only to find out when it was almost finished that it is never going to be fun without major changes. That’s a lot of time and effort wasted, and it would probably take you a long time to find out that you wasted it in the first place!

Seeing these benefits again and again in the assignments for the course, I decided to apply it to my vampire game project. I already had a basic idea of how the player will interact with the game. The player’s job is to find the vampire’s coffin, hidden in one of the buildings in town.

There will be a town map, and the player could move through the streets and enter buildings. Time plays a major part of this game, so there will be a sun moving across the top of the screen to indicate when it is daytime, and a moon will pop up when it is nighttime.

When it is daytime, the vampires will be in hiding, and the player can move anywhere. At night, however, the vampires will be out and about, and they are invincible. They move much faster than the player, too. There will be a single vampire at first, but each night he survives, he will sire a victim and add to his army. Basically, the longer it takes the player to find the coffin, the harder it will be to survive.

Well, the above sounded simple enough, but what happens when I try to play it?

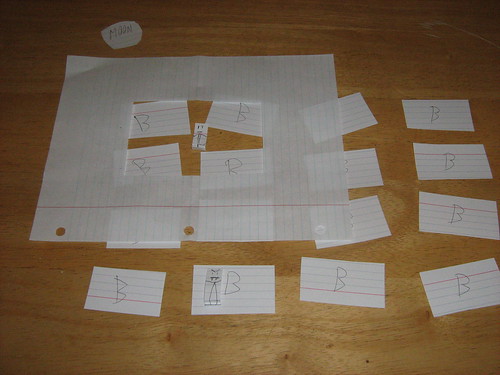

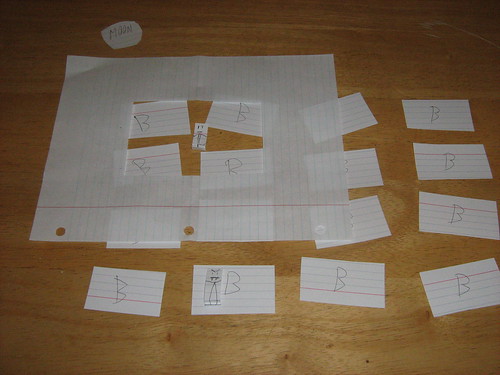

Above is my paper prototype. You can see the player at the northwestern part of town, and the vampire is hidden in a building at the southern end. The sun is out, and so the vampire is sleeping.

One of the first things I did was the simplest. Let the sun go down and see what happens. Right away, the player can see the vampire come out of his hiding spot. If the player can get inside a nearby building and survive until morning, he’s already won the game because now he knows where to find the coffin.

Huh. Well, that’s not what I wanted. For one thing, I want the player to seek out the coffin, searching each building in turn. If the player can simply wait for the vampire to reveal himself, there’s no tension and no fun. For another thing, I want the player to be afraid to be outside of the safety of a building at night. Staying out at night should be a good strategy for getting killed, not for winning. What could I do?

Aha! What if I limited the viewable part of the screen at night based on the player’s location?

Look at that! Now, if it is nighttime, and the player is outdoors, he can only see the immediate vicinity. If a vampire appears out of one of these buildings, the player probably won’t have time to get away since the vampires are so fast. Otherwise, the player has no idea where a vampire might come from. On top of that, the only thing a player would want to do at this point is find safety. The vampires will find you, and you won’t know where they are until you see one…and if you see one, it’s too late.

Another set of paper prototypes involved the building view, which helped me figure out what the player should be doing when hiding from the vampires. I’ve already started programming, but I’m still early enough in the project that these paper prototypes, which took me minutes to make and play, saved me a lot of pain and frustration. When I can only dedicate so much time in my week to this project, it’s nice to feel somewhat confident that what I am working towards isn’t broken in a basic way.