I’ve been writing about my lessons learned from past game jams. In a few short years, I’ve gotten better at finishing more ambitious games, and yet I still had a lot to learn.

If you didn’t read them, see my history of game jams part 1 and part 2.

Mini LDs

Between the major Ludum Dare compos, there are monthly Mini LDs. Usually someone hosts it and has the option of specifying special rules.

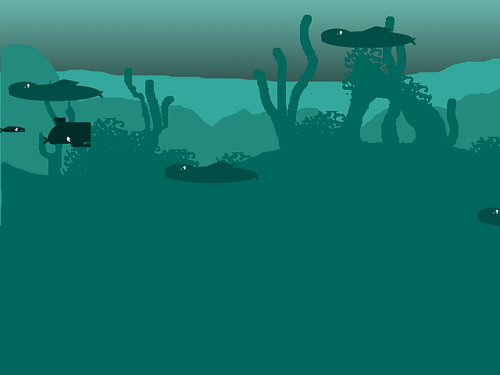

Apparently I didn’t blog about the mini compos I participated in. My favorite is from MiniLD #6 in 2009, which had the theme Monochrome and the special rules that you could only use a limited palette of colors. The idea was to combine all entrees into a single game. The other special rule was that each entrant also got a theme. I got Guardian.

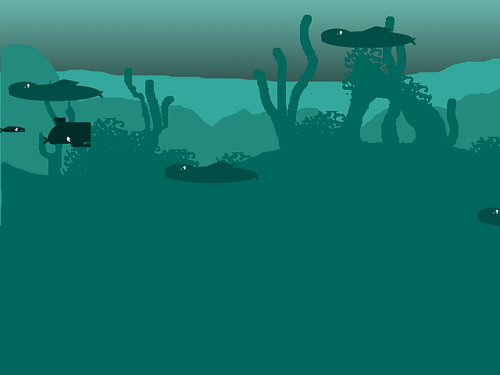

I’m not sure how the final result turned out for all the games, but my game was Guardian Fish. I didn’t even plan on participating that weekend, and yet I put together something that people have told me would make a great game for the growing iOS market if I fleshed it out.

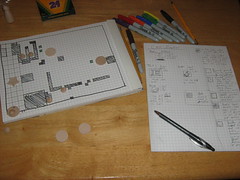

In 2010, right before Ludum Dare #18, I hosted MiniLD #20 with the theme Greed and the optional theme of Fishing with a special rule: “Only one of each.” While programming usually makes it easy to make exact copies of objects, I was insisting that everyone had to ensure there was only one copy of any object.

While there was some griping about the constraint, there were more entrees in this MiniLD than any before it, even though a power outage and my project’s overly ambitious scope meant I didn’t get my own game, The Old Man and the Monkey Thief, done in time. I should have paid attention to my own compo’s constraints and adjusted the scope to fit it instead of trying to create a bunch of content to get around it.

I wrote up a post-mortem of MiniLD #20, including both my own project and running a MiniLD.

It turns out that people want closure and it isn’t enough to simply start a compo and disappear.

My favorite piece of feedback:

I must say there were times when I wanted to stuff that glass of juice down his throat.

You can’t buy memories like that. B-)

It’s also when I met McFunkyPants on the Ludum Dare site for the first time. He’s a pretty awesome game developer, game jam enthusiast, and author, and he runs One Game a Month, an awesome challenge now in its third year.

Full-time Indie Jams

The MiniLDs are great practice for the main compo. I missed Ludum Dare #19 due to the holidays, but I was sure to be part of Ludum Dare #20. At the time, I was struggling with how long Stop That Hero! was taking and I wanted a quick win.

The theme: “It’s Dangerous To Go Alone! Take this!”

Ugh. Really? The meme won? Fine.

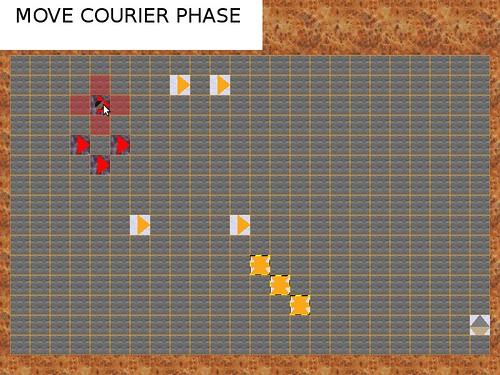

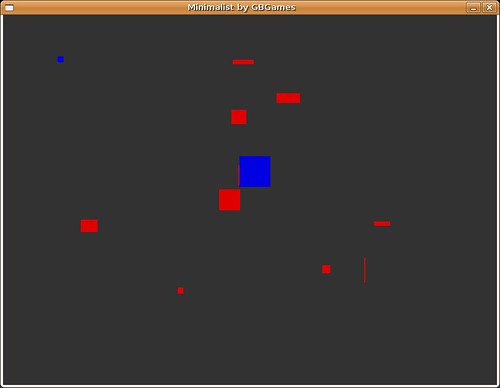

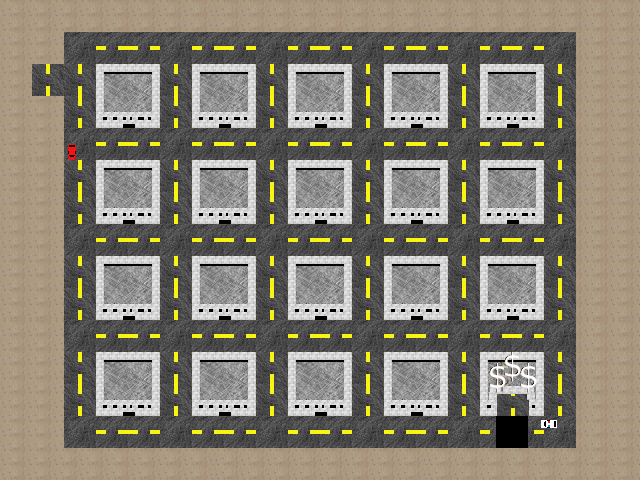

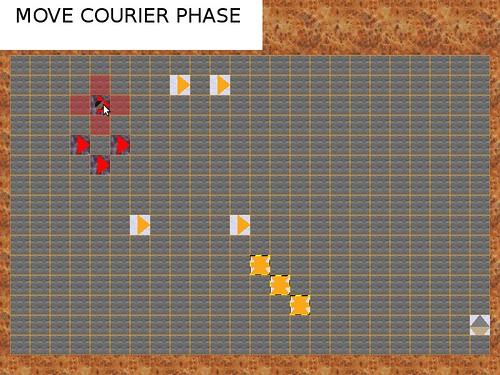

I had the initial design I went with right away, prototyping it and eventually making it happen, except I didn’t get it done in 48 hours, so I once again took advantage of the third day of the Ludum Dare Jam to submit Hot Potato!, a game of delivering a package while avoiding the agents trying to grab it. You can pass the package to an adjacent courier (the “take this!” part of the theme).

Once again, simple graphics meant getting things done more quickly, although I didn’t get nearly as much done nor as quickly as I would have liked.

It would be over a year before I would participate in another game compo. Ludum Dare #24’s theme was Evolution, the Susan Lucci of Ludum Dare themes that never won until it did.

I managed to have something playable very quickly, and I iterated the development well. I didn’t get everything I wanted, but when the 48 hours were up, I had something fairly solid to submit instead of trying to rush something that resembles game play at the last minute.

It turns out that Ludum Dare had been getting quite popular, and it has been hard to get people to rate games. In the past, you were given a random list of 20 games, and you were expected to do your best to rate at least those games. Now, they introduced a coolness rating, which increases as you rate other games, and it’s value determines if other people see your game when they get their random list of games that need a rating.

I didn’t plan on setting aside time to play and rate games, which hurt me in this compo.

In my post-mortem of Ludum Dare #24, I wrote:

If I could do LD#24 over again, what would I do differently? I’d spend more time upfront trying to create a design better suited for the theme that is also simple enough for me to make. I’d make sure my list of tasks was prioritized so that at all times I was working on implementing something that served the core design. And I’d make sure that I had set aside time after the compo and Jam to rate other games. People worked hard on their entries, and with over a thousand of them submitted, it’s unfortunately easy to get buried. I think the coolness rating does a great job of making things fair, and the name is perfect. I want to be cooler next time.

Another Long Absense Before the Next Compo

But it would be another two years before I participated in another game jam. By this time, I had a day job again, progress on Stop That Hero! was indefinitely on hold, and I had spent some long and dark evenings figuring out what direction GBGames should go in.

And I apparently forgot my previous game jam lessons.

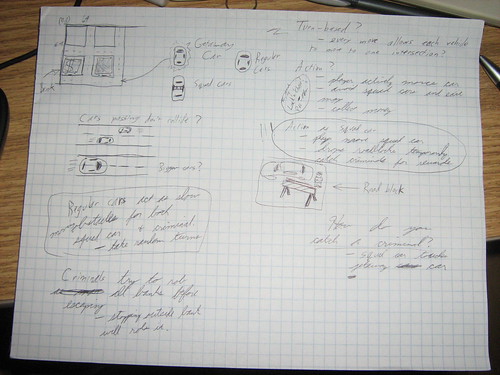

I came up with a lot of ideas for Ludum Dare #32’s theme, An Unconventional Weapon. Some of them were used by other participants to great effect.

I loved the idea I ran with, though: getting a giant monster to follow your character so you can lead it towards your enemies while avoiding death yourself.

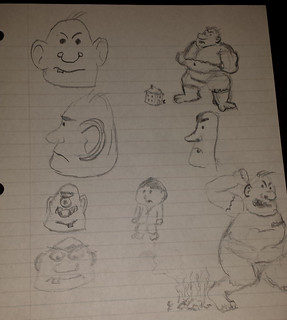

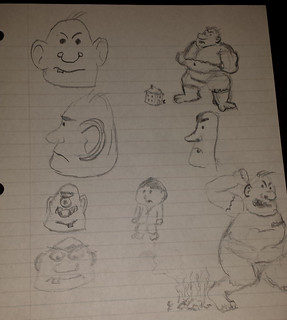

My strategy was to doodle when I wasn’t coding, and rather than use my poor digital art skills, I would use my less-poor pencil drawing skills and digitize them.

And then I threw out that strategy for some reason and tried to create sprites that face four directions, taking up the lion’s share of the time I spent on this compo.

What’s worse is that while the animation helped, it looked worse in screen shots and didn’t look much better in motion. So all that time I could have spent on actually getting game play in was wasted.

It was hugely disappointing Ludum Dare compo for me. You could say I was rusty, but I handled my pacing badly and focused on assets instead of game play.

At the time, I was hard on myself and felt like it was proof that I still suck at game development. On the other hand, a few years ago, I would never have been able to quickly put together the limited game play that I did. I had a character that moved where you clicked in a very intuitive way, which is something people complimented me on, and I had a monster that you could attract either by getting in its vision or yelling out to it. The animations helped make it easier to see where the monster was looking, but I could have simplified them and had something working much faster.

So to be fair to myself, yeah, it sucked I didn’t submit a game, but I’ve come a long way from FuseGB and my first game jam.

Immersed Learning Experiences

My time working as a full-time game developer were definitely very good in terms of how much skill I developed and experience I earned in a couple short years, but the next best thing is a weekend dedicated to creating a game.

When you fully immerse yourself in the work, and when the constraints are that you need to have something finished in a short amount of time, you don’t get to procrastinate or be idle. You don’t read how to do things.

You spend your time doing.

And in the end, you have either a completed game that never existed before or experience to leverage for next time.

Getting that game finished is a great feeling. You get to point to a real game and say, “I made that. I’m a game developer. I developed a game.”

I’m looking forward to the next game jam. It’s another opportunity to grow with an entire community of game developers.