Recently I volunteered at an event in which I facilitated a simple math game for 10 minute sessions with a rotating group of children ranging in age from 4 to 7 years old.

The event I volunteered at was a celebration for refugee children who had just finished taking one of their last math tests in an educational program. There were math-themed games and a potluck after.

We had about eight game stations, each of which consisted of a simple math game at a table with a few chairs and at least one facilitator. Some of the games were made up by the educators volunteering, and others were given or found online.

An Incomplete Game

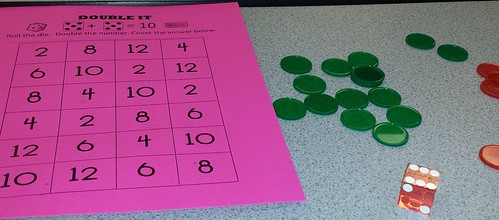

I was assigned a game called Double It.

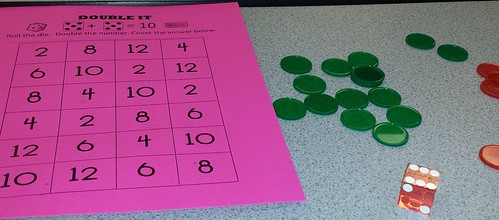

It consisted of a die, transparent markers in two colors, and a sheet of paper with a 4×6 grid of even numbers between 2 and 12, with each number repeated four times and placed in some arbitrary order.

I took some time to look at it before the event started. As a game developer, I immediately noticed a problem with the game: the rules weren’t comprehensive.

“Roll the die. Double the number. Cover the answer below.”

So, what’s the victory condition? I felt like maybe it was implied, but there were a number of variations I found that could work in this format.

If it was a square grid, then it could be math-based bingo card, but it wasn’t a square grid. Maybe whoever gets the most markers on the board wins?

But then I realized that with only four copies of any one number, there was going to be a situation in which a player will roll a number, double it, and find that the answer is already covered. What then?

I hesitantly asked the obviously very busy organizer of the event, who said, “Well, just let them roll again.”

Ok. Seems satisfactory.

And immediately after she left to continue her work, I realized that the game would then always end in a tie.

I had mere minutes before the event started, but I was not happy with this game.

On the one hand, I get it. It’s less about the game and more about teaching math skills. It doesn’t have to be an award-winning game. It just has to be a framework to let them practice within it.

On the other hand, the point of it being in game form is to be a compelling experience. As it stood, maybe the children wouldn’t recognize that it was a foregone conclusion that it was going to end in a tie, and maybe they wouldn’t see there was no challenge or conflict involved, but it seemed like chocolate-covered broccoli, and I wanted to do better for them.

Game Design in Five Minutes

So I gave myself the constraint that the original rules had to be the base of the game, but I set to work to make it a real game.

Given that Double It was supposed to be for 1st graders, I made sure not to get carried away with complexity. There’s no sense in turning this game into something like Vlaada Chvatil’s Mage Knight. In fact, with mere minutes to do this work, I only had time to do some simple tweaks.

Luckily, I got a chance to playtest with one of the other facilitators, and it really helped to talk about the rules changes aloud.

So here are the new rules I added:

- If a player has all four answers covered, then he/she has a monopoly on that answer.

- When trying to cover an answer, if there is no uncovered answer, and if the opposing player does not have a monopoly, then the player must remove the opponent’s marker from an answer and can place his/her own marker on that answer.

- The winner is the player with the most markers on the board once the entire board is filled or time has run out.

The second new rule adds conflict and actually allows for the victory condition described in the third new rule to be met. The first new rule came about as a way to reward the player for getting all four answers, as it seemed like there should be a way to prevent the opposing player from taking your markers off the board.

Playtesting

So how was this game? Well, luckily I had a rotating group of playtesters to let me know!

When each game session started, I found that the children were relatively quiet. Some of them were able to double numbers effortlessly, and it was fascinating watching them quietly roll the die, place a token, and pass the die to the other player. Some had more difficulty and needed help, so I held up my hands and tried to let them visualize what it meant to take a number and double it. In general, this early game was somewhat compelling on its own due to the math and it being a novel set of rules.

But once the board started getting filled up, my new rules came into effect, and I was pleased to see eyes lighting up and smiles breaking out. Some of the children got really animated, and you can tell the engagement level changed. Now they had a reason to pay attention to their opponent’s die rolls, and there was this sense of protection over the board.

I was worried that someone would get upset that he/she had a marker “stolen” by the other player, but instead I saw sheepish grins, which surprised me. Even losing felt fun, apparently.

End Results

Given the very little time I had, I think I did fairly well. With some more design iterations, I might have been able to add some skill and decision-making into the game.

The end result is determined by die rolls, much like how the card game War is determined by the order of cards distributed. There was no skill involved, and so my game still lacked something to make it truly a game.

On the other hand, it still seemed more compelling to add conflict to the game. There was a sense of risk, which gave the players a sense of ownership. That they had no control over what happened may not matter as much for a game for children.

The Future

If I wanted to continue to iterate on this game design, I would start with allowing players to choose between covering an uncovered answer and taking an opponent’s covered answer. Now randomness isn’t the sole arbiter of the game. The players would have some agency, and it could make monopolies feel like a real accomplishment, but I feel like there should be a risk involved in not taking an uncovered answer.

Also, I found the grid layout seemed to bias people to expect it to be a bingo-like game, and so I would change the layout to remove that expectation.

Of course, designing a game for children means that the game doesn’t need to be more complicated than it originally was. Maybe. Perhaps if it got too lopsided, one player would stop wanting to play. This is why playtesting with real players is important.

The original focus was on doubling numbers, and I wonder if educational games work better when the educational aspect is presented as a prerequisite for playing in a subtle way.

That is, now doubling numbers was something you had to know how to do in order to play, and it was not presented as the entire focus of the game. Children who struggle with math seemed to be nervous about the early part of the game, but once the new rules kicked in, I noticed they were more quickly getting through the math part so they could see what happens next. It was as if they had found a higher level reason for bothering to do math rather than just doing math for its own sake.

It’s like learning how to read in order to better play The Oregon Trail or learning how to count to play Candyland. These games weren’t ostensibly about learning how to read or count, but as you played, you HAD to get good at those things in order to play the game better.

Another bit of evidence for this kind of education is also anecdotal. On my Apple II C+, I had Stickybear Typing, which was supposed to teach me how to type. I didn’t like it much. Yet, when I learned how to program and started trying to get the computer to do things for me, I found myself practicing key presses to the point that one day I didn’t have to look at the keyboard. Typing was a skill I picked up because I had a context in which to do the typing. When typing on its own was the goal, I struggled.

As I’m not an educator, anyone know if there is already a name for this kind of learning/teaching?

Credits?

Thinking about exploring this game’s design made me wonder where the original game came from.

A quick search online shows that Double It seems to be Doubles Aren’t Trouble, which is a freely available exercise from Jennifer White’s First Grade Blue Skies. The name and design of the paper is different, but the layout of the numbers and the initial rules are exactly the same. White has a number of free and for-sale resources for the classroom, including games and craft exercises for a variety of grade levels.