In the past, my game development project plans have been little more than to-do lists of tasks and features. I had no real deadlines and no idea when anything would be done. I basically picked a date for the entire thing to be finished without any real sense of how realistic it was, and then I worked on whatever task I felt like working on until I felt it was good enough to move on to the next one.

And then I would blow past my self-imposed deadline, feeling frustrated about how much work I still had left.

I mentioned that I will be focusing on impactful results over progress in 2016, and to help me do so, I decided to create a more detailed plan for my current game.

That plan covers what I’ll be working on and completing for the next three months. I want to release a playable game to at least one player, whether it is a customer or an alpha or beta tester, at the end of March.

I fully expect this plan to be a living document that changes as I identify new requirements or tasks, finish things early or late, and learn more about what I’m making.

Creating this plan was tough at first. I struggled with how to start, and even started searching online for project planning articles.

Then I realized I live and breathe Agile software development, and Agile project planning is a thing.

I’m normally on the tail end of the process, though. At the day job, my team estimates the effort on user stories, breaking them up into tasks if they are too big. We work in two week sprints, and planning the sprint is based on how much effort we as a team think we can accomplish during that time. So, as a developer, I am usually working on directly creating the software that someone else needs me to make, and while I have input to tweak or change requirements (“We can’t do it that way because it will cause problems with the existing architecure. How about if we do it this way instead?”), I don’t generally have the ability to decide what project the company is working on.

For my business, I needed to start from the beginning, and creating this project plan was a great exercise and gave me quite a bit of insight into what I’m actually going to be doing when I say I am working on my game.

I thought about signing up for a service such as Trello or downloading an open-source project planning application, but I decided to create a simple set of spreadsheets. I already have LibreOffice on my computer and didn’t want to sign up for yet another service. Since it’s just me working on this project, it doesn’t need to scale much, but larger teams might need something they can share and update at the same time.

The plan has five parts to it: a product vision statement, a project backlog, a roadmap, a release plan, and the current sprint.

Product Vision

DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP!

This part I already had, but it’s such a key aspect that I wanted to focus on it for at least a few words.

Nothing kills motivation more than not understanding what you’re working on or why you should be doing so in the first place.

A clear statement that defines what the project is, who the audience will be, and how this project supports the overall strategy for your business does wonders for your mental energy and focus.

I can’t emphasize this part enough. I used to gloss over the boring idea of a vision statement or defining a clear mission for your business that I read in pretty much every book about running your own business, productivity, and effectiveness.

Think about it this way: you need to take a trip. How will you travel?

Without a vision or a mission, any mode of travel is a viable option, right? If you want to travel by ocean cruise, you can do so. If you want to fly, you can do that, too. Driving might also be a completely valid option. Heck, not going is fine as well. You don’t really have a wrong answer possible here.

But there isn’t a right answer either.

Now imagine that this trip is an emergency. Someone you care about is in trouble, and you need to go save him/her. A luxury cruise seems like a poor option, and not going at all is pretty much thrown out as an option. Flying is faster, but driving gives you flexibility in travel at the destination. Hmmm…

What’s the difference between the two scenarios?

What happened is that the emergency gave you context for your trip. You had decisions to make in both cases, but in the emergency, your decision-making became instantly easier because options were eliminated and you had criteria you could weigh the remaining options against.

One of the biggest jobs you have as an indie game developer and business owner is making decisions. Without a vision, a purpose, or a mission, your decisions can be random and take you anywhere.

So establishing a vision for your project gives you a high-level context within which you can make key decisions.

My vision for this project involves publishing a simple educational Android game to get more first-hand knowledge about potential customers on that platform. I’m not talking about personal information. I mean I always hear about how Android users are not willing to pay for games and that iOS is a better platform, but I want to confirm this data with MY games and not just the flood of games of varying quality in the market.

My principles for this project include that it should be educational, family-friendly, and have an accessible interface.

I changed my approach with this project last year because I realized the physics simulation I was working on didn’t serve the educational aspect of my vision.

Without a vision, I would have no direction. I could easily have kept working on the physics simulation version of this game because it was fun to try to get leaves to move in the wind just right; unfortunately, it would have been a waste of time as it doesn’t serve my vision for my business as a whole.

Establishing a clear vision for your project and ensuring that it is in alignment with the vision you have for your business (you have one of those, right?) is a hugely important step. It gives your project the context you need to make decisions easier.

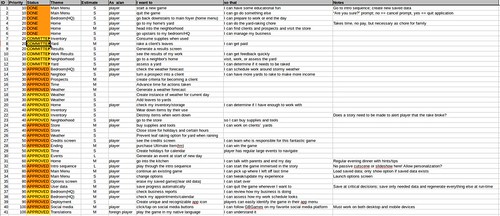

Project Backlog

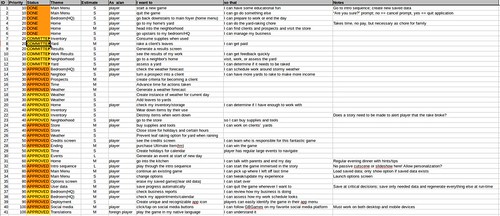

The backlog is basically a prioritized list of features. It’s slightly more involved than the to-do lists I complained about earlier.

The project backlog was fairly easy to make. I thought up a list of features I wanted and wrote them down.

The tough part was writing some of these features out as user stories. I found Mike Cohn of Mountain Goat Software has provided a sample spreadsheet-based product backlog, and I created my backlog based upon his recommendations. Cohn’s website has a lot of great articles on user stories, backlogs, and project planning, by the way.

He recommends the format: “As a <role>, I want to <do something> so that <business value>.”

By focusing on the player’s experience when planning this project, I am less likely to get mired in a fascinating technical problem for months. Not that those fascinating technical problems won’t happen as part of a user story, but it’s like having mini-vision statements to give context to your work.

The context of a user story around a technical problem should sharpen my focus on accomplishing my bigger goal as opposed to merely geeking out over a hard coding problem that my players won’t care about if I ever finish the game in the first place.

Writing such stories is hard if you don’t have experience with it. It’s easy to write user stories that are not really user stories or don’t really do a good job of explaining what the work is meant to be. Just following the format above isn’t enough.

As an example, here is how I started writing the Main Menu theme’s stories:

As a player I want to launch the main menu so that I can start a new game

As a player I want to launch the main menu so that I can continue an existing game

As a player I want to launch the main menu so that I can quit the game

As a player I want to launch the main menu so that I can change options

But it felt awkward and forced. The main menu is what comes up when you start the game, so there it’s actually more of a passive event. I’ve basically taken the notes I made myself “Create a main menu with four options: new game, continue, quit, and options” and tried to force them into a user story format.

Thinking about it some more, I made them better by focusing on what the player was doing and the real benefit or reason why:

As a player I want to start a new game so that I can have some educational fun.

As a player I want to continue an existing game so that I can pick up where I left off last time

As a player I want to quit the game so that I can go do something else

As a player I want to change options so that I can tweak/update my play experience

I kept writing, tweaking, and deleting features and stories until I couldn’t think of anything else I needed. I ended up with 41 stories for this project.

The next step was estimating them. At this stage, there is no point in trying to estimate each and every story accurately. After all, we suck as a species at estimating. I don’t expect to be 100% correct, but this exercise should help me identify roughly how large the project is.

I used the common project planning estimation technique of using t-shirt sizes. Stories were estimated as Small, Medium, or Large.

Finally, I prioritized the entire backlog. Given what I know about the project so far, what should be finished first? What’s less important and can wait? The idea is that whatever I’m working on is the most valuable thing at the time, and yes, I fully expect that priorities can change.

I used values spaced out by 10 so that future stories can be prioritized in between existing stories.

The most important features were assigned 10, and the least important 100, and all stories fell between those two values. Some stories shared the same priority value, mainly indicating that they should be done together.

I didn’t purposefully use numbers between 10 and 100, but it worked out that way. If I had more stories to prioritize, I probably would have kept increasing the maximum priority value beyond 100. You could use whatever values make sense for you, but the main idea is to have everything in your backlog ranked based on priority.

Just by prioritizing and estimating the backlog items, this project plan puts my past project plans to shame. I know at a glance what is important, what features I’ll be working on first, and how much effort I expect they will take. This information is good to know.

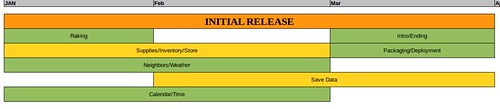

Project Roadmap

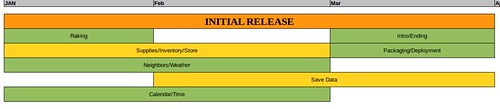

A roadmap is a rough timeline explaining when certain parts of the game project will be worked upon and when they can be expected to be finished. It’s not about features so much as what value the project will have at different times throughout the project’s life.

I’ve never made a project roadmap before, so I needed to do some research. It wasn’t that difficult. I already estimated the effort needed for the known features in my backlog, and they are already prioritized. I basically needed to look at groups of my priorities and identify high-level concepts based on my features.

I had to take my t-shirt estimates and apply them to a calendar somehow. I have no historical data as I’m starting a fresh project, and so I don’t know how many features I can accomplish in a given week. As someone with a day job and a family life, I only have so much time to dedicate, so things that might normally take a developer a day or two can drag out for a week or more split across multiple short work sessions.

So I guessed that Small features should take me about an hour, Medium stories are about two hours, and Large stories are likely going to need to be broken up into smaller tasks I can estimate as Small and Medium stories.

And given my goals for weekly development hours, I can figure out which features and stories will be done when.

My game puts the player in the role of a child who is raking leaves to earn money. There are a few stories and features around the raking mechanic. Since raking is such a key part of the project, it’s one of the first things I want to finish early. I say finish even though I know game projects can change in development and I might change how it works at any time based on experiments and playtesting, but my roadmap shows I will have the raking mechanic done this month.

Raking requires neighbors and their yards, and so I will also start working on the neighborhood this month. Since I have a number of features involving them, some prioritized later in my backlog, I know I will need to continue working on this aspect of the game through to February. My roadmap reflects this knowledge.

Creating the roadmap helped me tweak the backlog priorities, and the backlog’s priorities helped me create the roadmap. I bounced back and forth between these two sheets in my project plan’s spreadsheet file until I felt I had the priorities and rough scheduling right.

And there it was: a visible communication to Future Me about what I wanted to accomplish with this project and by when.

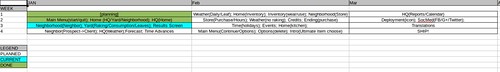

Release Plan

A release plan explains at a high-level how you intend to deliver working software at the end of XYZ sprints. That is, some teams work for multiple sprints before producing a release. Others strive to ensure their software is always in a releasable state.

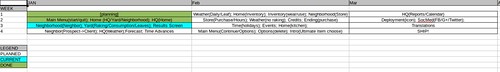

I decided to “release” weekly. That is, at the end of a week, I expect to have my game at a certain level of functionality identified at the beginning of the week. So my release plan identifies what I expect to work on each week from the beginning of the project until my expected release at the end of March.

It doesn’t say exactly what I’ll be working on. That is, it’s not like I’m planning exactly which specific stories or features I’ll be working on between February 14th through the 20th.

However, that week I will be working on adding the concept of holidays to the game world’s calendar, which influences things such as whether the general store is open or if neighbors are out of town. I will add a new room to the player’s home that has specific functionality available. And I will also be working on a Large feature that I have designed as a game mechanic. By the end of the week, I expect all of those things to be done.

But I don’t necessarily know what those things should exactly look like today. I don’t have them planned as a set of tasks to work on yet.

And that’s OK. When I get to that week, the project might have changed so significantly that this feature is no longer relevant. I won’t waste time planning the specific work involved until that sprint is my next sprint.

Just like how changes to my roadmap and my backlog could impact each other, my release plan helped me figure out my roadmap.

Given my current estimates of both my backlog and how much I could accomplish in a given week, my roadmap had to be adjusted a few times. At a high level, I overestimated how fast I can finish a given set of features, and my lower-level release planning helped me see it and correct it.

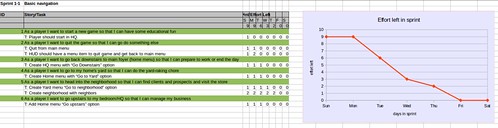

Sprint Planning

Now I have a prioritized backlog, a roadmap to show me how my project will develop at a monthly level, and a release plan to show me what I’ll have accomplished on a weekly basis.

The next thing to do is plan the next sprint’s worth of work.

I first give the sprint a name. Maybe it’s not that important, but it’s another layer of context. What am I trying to accomplish this sprint? A good name helps me remember when I’m waist-deep in the work.

Here is where I take the stories I initially wrote and ask myself questions. Stories aren’t meant to be detailed project documents but invitations to a conversation, but since it is just me, I have the benefit of knowing what I mean but the disadvantage of not necessarily remembering or having thought of the details.

Sprint planning is when those details come out.

For instance, when the player selects New Game from the Main Menu, what exactly should happen from the user’s perspective? In the future I have planned to create a playable introduction to the world of the game, but I don’t want to work on it until I have the core game play down. So I specified that for now the player will start out in his/her bedroom. Suddenly this story requires the task to create an in-game bedroom.

I took each of the stories I planned to work on and broke them into as many tasks as necessary to make it clear to me what I specifically needed to do to say the story was done.

I don’t need to specify a lot of detail before I can start working. If something comes up that I hadn’t thought of before, I’ll make a decision then. You want to plan enough to know what you’re doing but not so much that you waste time on details you can’t possibly know the answer to until you face them.

I estimated the tasks based on hours I thought they would take to accomplish. I didn’t try to get it down to the minute so much as I tried to get a feel for how much time it will take me to get this week’s work done.

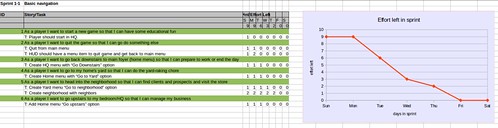

My first sprint last week was estimated at about nine hours of work. Some tasks were done within minutes and others took much longer than expected. I ended up doing only 5.5 hours of game development to get all of this sprint done, so I was a bit off.

Each week I’ll do sprint planning again, and over time I’ll get a better feel for how much I can reasonably accomplish in a week’s worth of effort.

Was It Worth It?

Creating the initial plan took me only about a day’s worth of effort, although it was spread over a week’s worth of shorter sessions for me. Each week I can expect to invest some time in planning the next sprint, and each month I expect to spend some time updating the plan as a whole.

That’s quite a bit of overhead for a plan that is subject to change, especially with my limited, part-time efforts. The plan is also somewhat incomplete as it assumes I will be working on the project without interruption. I could get sick, and there is bound to be a weekend trip to visit family in the next couple of months that throws off my release plan if I don’t take it into account.

But even this early in the project it has been incredibly valuable to me.

Having a high-level roadmap and release plan helps me focus on my priorities. Instead of having a vague sense of wanting to finish a game and a list of ideas masquerading as features, I know what my next few months will look like in terms of my daily effort. My work for the day, the week, and the month has a much clearer context than ever before.

I am able to focus on my features from the perspective of the player as opposed to the perspective of me wearing the developer hat, which means my development will be more purposeful and effective. I will always know why I am working on something, which should help me be more conscious with my development choices. I should be less likely to find myself at the end of a year without a game published because I didn’t realize I was spending too much time on some neat algorithm.

And I have a reasonable level of confidence that I will create a first release of my game to at least one player by the end of three months. It will likely still be rough, with perhaps quite a bit of polish needed, but my goal is to get a release out then, and my plan shows me a way to get there.

In the meantime, I also have smaller planned releases of new functionality to test and get feedback on. For example, just by posting a screenshot of my project at the end of the first sprint I got some comments on Twitter that made me rethink the UI element I was using.

While I still believe in low-overhead, lightweight plans over intimidating 300-page documents no one will ever read, I think my past plans were too light to the point that it would be considered generous to call them plans. They didn’t help me figure out what I was doing or assist me in making decisions about the project. This project plan, however, has already helped me quite a bit, and I’ve barely started.

So yes, I believe spending time as a part-time indie game developer on detailed project planning was worth it.

Sources

I did a bit of research as there were aspects of this type of planning I had never done before. Here are some great links I found to articles, book chapters, and other resources that I found valuable:

Quarterly Planning Time and More on Planning by Steve Pavlina: some old articles on the importance of planning. He also had a recent newsletter in which he promoted the value of creating detailed, long-range plans.

Agile Project Management for Dummies Cheat Sheet: I’ve heard good things about For Dummies books. Although I haven’t read this book, the cheat sheet gave me a good overview and summary of the project planning process.

Mountain Goat Software by Mike Cohn: There are so many good free articles here that give you an overview of many aspects of Agile project planning and Scrum.

The Art of Agile Development: Release Planning by James Shore: This chapter portion focused on release planning, and I found it helped me understand what I was really trying to create with my release plan. There is a common idea of the “last responsible moment” to break down things into details, and this resource does a good job of talking about it.

How to do Agile Release Planning by Kent J. McDonald: Another article on release planning with links to quite a few resources on the topic.

We Need Planning; Do We Need Estimation? by Johanna Rothman: A quick read about the idea that detailed estimates aren’t a good use of time. You want to work on the most important thing and deliver results incrementally and iteratively. “This is risk management for estimation and replanning. Yes, I am a fan of #NoEstimates, because the smaller we make the chunks, the easier it is to see what to plan and replan.”