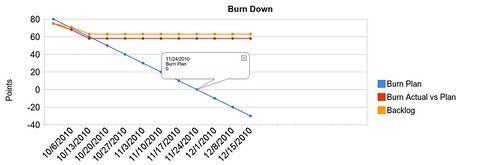

The last major progress update for Stop That Hero! was in November (see Stop That Hero! November Development Summary), so I thought I’d post about my progress since then.

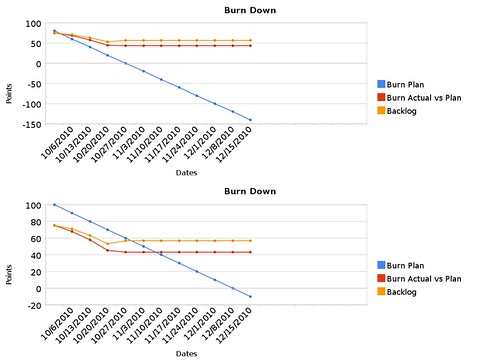

Between moving, prepping a new office, unpacking, and not realizing how much time was passing, I messed up my project management duties in December. Combined with Christmas and family time, there is very little to report, and I finished 2010 weakly.

January, on the other hand, is looking much better. Here’s an outline of the things I’ve worked on in just the last two weeks:

- Integrated pathfinding system with game.

- Created Command system to populate game world with game objects.

- Updated level definition.

- Re-architected the rendering system.

- The Hero can clear towers!

Let’s dig into the details!

Integrated pathfinding system with game

The nature of working with unit tests is that a lot of features get implemented in a vacuum. The code you’re test-driving is interacting with interfaces implemented by mock objects to see if specific, isolated examples run as expected.

Sometimes surprises occur when the new features are integrated with the rest of the production code.

The pathfinding system was one such feature. Everything technically worked, but when using real data, I realized there was a problem.

In my unit tests, I would check if the path gets updated when an entity was at an exact node location.

In the game, the exact center of node (10, 10) is at position (10.5, 10.5), and I didn’t realize how it would look when an entity moved to node (10, 10) by trying to get to position (10, 10).

Even when I got things working and looking correctly, I found a problem. An entity moving through a long path would eventually miss its next target node and continue moving away in the same direction it was last moving. It was a precision problem. Again, an entity was rarely at an exact node location. The entity might be a little further away. Eventually the extra precision adds up to being completely off target.

To fix it for now, I just force the entity to jump to the exact center of a node once it reaches near it. It’s a little jumpier than I would like, but the entity is never allowed to lose precision and be off path. I can correct it later, perhaps with a better implementation for movement, but for now, pathfinding and movement is functional enough.

Created Command system to populate game world with game objects

When a level was loaded, it would make use of an image like the following:

It’s blown up to make it easier to see, but the real data is a 50×33 PNG. Different colored pixels would represent the terrain, and I also used the pixel color data to create the towers, treasure chests, and hero’s starting spawn point.

However, level-loading time isn’t the only time objects can be created in the game. During a game, the player can create monsters, for instance, and I’m interested in the idea of letting the player create towers instead of being handed them at the start of a session. Also, it was awkward to have the level loader code know so much about all the different kinds of objects that could be created. There was a function to create the Hero entity, and I didn’t like the idea of lots of functions for each type of game object to create.

So I created a Command system. I suppose most game developers call them Events, but the point is that I pushed the responsibility of creating game objects to self-encapsulated pieces of code that can be created and passed around.

So now when the level loader pulls in object data, it requests commands depending on the data. For example, a white pixel specifies a basic Tower, so it requests a CreateTowerCommand. When that command is executed, the game world has a fully functioning Tower.

If I allow the player to build towers or if there is any reason why a tower should get built after the game session starts, it’s a simple matter of requesting a CreateTowerCommand.

It’s pretty powerful stuff, and I wish I had thought to do it long ago! I have commands to create the Hero entity, the towers, the castle, and treasure chests, and as new features get added, I find this command system provides an easy way to centralize and encapsulate certain activities.

I’m sure there are ways to improve it, but for now, it’s working well.

Updated level definition

If a tower is represented by a white pixel, by default the terrain around it is defined by other pixels. A tower spans multiple tiles, but the pixel’s location defines only the entrance of the tower. How do I get the terrain around the tower entrance to act like obstacles?

In the end, I didn’t solve this problem yet, but in trying to, I realized something wrong with my level definition. I was trying to use a single piece of data to define two different things.

I took the level PNG and split it into two. One PNG defines the terrain, and the other defines the objects that should exist in the level. In the image above, the white, red, black, pink, and yellow pixels are in a separate PNG associated with the level.

At the very least, now it is easy to define what the terrain around a tower looks like without worrying about the ability to define the location of the tower. I suppose I could have used the same image in a different way, but again, this works for now.

Re-architected the rendering system

At some point, I realized early architectural decisions were making it hard to separate the player’s interface with the game from the game. While I managed to get the game simulation well structured and easy to work with, I had a messy implementation for rendering, and I had no easy way to implement a UI.

I explained how I got sprites rendering in the correct screen locations based on their in-game world position in Stop That Hero! Sprite Rendering Questions, but the problem is that the sprite objects were mixed into the game’s object model.

Now, imagine switching resolutions on the fly. If the sprites are all there, they have to be replaced by more appropriate sprites. And rendering requires an updated viewport to deal with the new screen resolution.

Now, what does the simulation care about how it’s being rendered? Nothing! Or at least it shouldn’t!

It took a bit of refactoring, but not a lot. I was able to leverage what I had to get to a new solution.

I now have a concept of a View. Now, I’ve looked into Model-View-Controller, and quite frankly, I didn’t think it worked very well for what I was trying to do. This isn’t a simple application with buttons and a database.

But I did like the idea of a separate view and something to process player input. The input processor is still missing, but there is now a View that handles rendering using data from the game world but without being part of the game world.

Or at least, it will. Right now, Sprite data is still part of the entity, and I’d like to change it so that the View worries about Sprites while the game objects have RenderableComponents which merely describe what Sprite the View should get. So if a Tower has a RenderableComponent that says “Use TowerSprite”, then the View can get TowerSprite out of the 800×600 sprite collection or the 400×300 sprite collection, depending on the View’s resolution.

The Hero can clear towers!

For some time, the Hero had the ability to target Towers, find a path to the nearest Tower, and move to it. But then he’d stand there. It was still the nearest target.

It didn’t take me too long to implement a way for the Hero to change the Tower’s target status. Basically, the game had to detect that the Hero was in the Tower’s entrance, and then it requested a ClearTowerCommand. That command will get more code eventually as more features are added to the game, but for now, it takes the Tower’s Targetable component and deactivates it.

Now, the Hero moves to a Tower entrance, and then he searches for the next nearest Tower until there are no more left. While the implementation details could use some cleaning up, this mechanic is such a central part of the game, and it’s great to finally see it in action again.

Conclusion

My last two weeks have been quite productive, and I wish a screenshot could show it, but most of the work is under the hood. Still, simple infrastructure work has already paid off in implementing some game mechanics more easily. I’m pleased with my recent progress.