Halfway through January I gave a progress update for Stop That Hero!, and in the two weeks since, I’ve accomplished a fair bit.

Recap

In the beginning of the month, I did work to create a command system, separated the game’s simulation from the rendering of it, and even added some game play related to the Hero conquering towers. There were other things accomplished, but they were slight changes compared to these major pieces.

Treasure Collection

Since then, one of the things I worked on was treasure collection. Items can be collected, which basically means running an arbitrary command. Since I don’t have much game play in, there isn’t much implemented in this regard. Right now, if the Hero comes across a treasure chest, it just disappears. Well, actually, it has its targetable component turned off so that the Hero ignores it, and it changes its renderable component so that it draws something other than the treasure chest sprite.

Why? Because I haven’t needed to delete game objects before, so there’s no way to do it. Also, I apparently never needed to hide sprites before, so there’s no way to do that, either. The “hacks” are functional for now, so I can move on to other things. I’ll come back to change these when I need to, and I may be surprised to find that I won’t need to. I already do enough unnecessary work as it is, so there is no need to add to my burden. B-)

Enemies

The next major thing I did was create a slime monster to chase after the hero. With the command system, it was as easy as creating a new command which populates the datastore with components that make up that monster. I simply took the CreateHero command, did some copy-and-paste magic, then modified its speed and the renderable component. Now I can create a slime as easily as a Hero!

Except I had no way to interact with the game yet. How did I test that the command worked? I changed the level loading code. Any treasure chests or towers defined in the level would create slimes instead. When I ran the level, the Hero had to find his way to the Castle past an entire army of slimes slowly approaching him like zombies!

Once I was satisfied that the new Slime would work within the game, I changed the level loading code back.

Front-end Architecture

The game simulation is well-defined and is easy to update. If I want to add a feature, it can be as simple as creating a new UpdateSystem, perhaps with associated components that entities can make use of.

As happy as I am with the internals of the game, I was getting frustrated with the user-facing parts. Getting from initialization to the menu to the level selection screen to the game session was poorly-defined and hard to change. I haven’t even provided a way to quit the game outside of clicking the application window’s X. When I wanted to work on providing menus for the player to click on in-game, I realized I had to do something about the front-end if I was going to make the UI work easier on me.

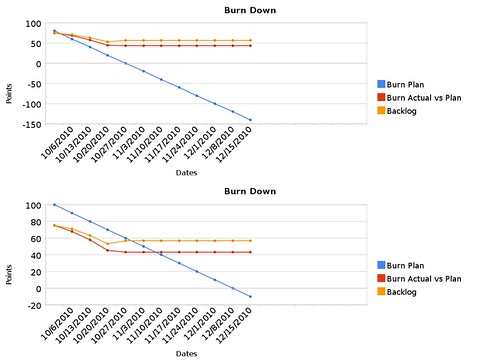

Here’s how my application’s architecture looked:

As you can see, the game took up the lion’s share of the application. There was no concept of screen transitions or anything like that. You were either in a complex menu, or you were playing the game. I had no concept that a game application was anything other than a game.

I spent a few days figuring out the approach I should take. I didn’t realize that my game isn’t everything at first. It’s a tiny part of the full application. To flesh out that application, I settled on creating a state machine. I don’t know why I didn’t think to do it before. I’ve done it for Game in a Day back in 2005.

I spent a few days coding up an implementation of a state manager, and I spent a good chunk of my time at the Global Game Jam getting individual states implemented. My application is now run by a high level state machine, which looks close to what I designed on my white board.

In fact, something like this has been scribbled down multiple times in notebooks and scrap pieces of paper every time I stopped to think about the high level, and it is only now that the state machine is actually implemented.

Also, note that there is one state I call “In-Game Session”. It’s in this state that the game runs. In terms of number of states, it only makes up about 10% of the application!

And additions and changes are easier now. If I wanted to add an Options screen, it would have been difficult to shoehorn it in my old architecture, but now I can simply create a new state. It’s kind of like programming tiny applications that work together.

Now the application’s front-end feels as good to work with as the game code, and since it makes adding and updating application states/modes so easy, I wish I had implemented the high level state machine in the first place.

User interaction

As great as all that rearchitecting is, I still didn’t have a way for the player to interact with the game simulation. Without interaction, it’s not a game.

So how do I add interaction?

Well, it’s the part that I don’t have working yet. Here’s how I approached it so far:

I have the game running as a LevelInstance, which has a collection of UpdateSystems and the database of game objects/components. I created a View that has a collection of RenderingSystems and access to the LeveInstance object.

I didn’t use Model-View-Controller because I didn’t feel it was a very good fit based on my understanding of how it would apply to a game.

If you’re familiar with MVC, the LevelInstance is the Model. So the V part of MVC is obvious, right? Not exactly.

My View is quite dumb. All it does is get information from the model and render it. The game simulation doesn’t care how it is being rendered, and in fact, I can have multiple views attached to a running game.

Ok, so far, so good. What about the Controller?

If you read about MVC, you don’t typically put business logic in the Controller. If I was making a game where you controlled an avatar with direction keys and a jump button, I think I could make things work fairly easily. The Controller would detect button presses and send commands to my game that make sense. For example, if I press the Spacebar, the Controller maps that to the Jump command, and the model knows that the player should jump, never caring that the Spacebar or another key was pressed.

But in Stop That Hero!, you’re not controlling an avatar directly. You are clicking UI elements. Here’s how I envision the player’s interface:

When the player clicks on a tower he/she controls, a pie menu appears around that tower. Each of the four items represent what monster can be created.

Here’s where I’ve been struggling.

If the View knows nothing but to render what’s in the model, and the Controller simply handles input and processes commands, who owns the in-game UI? Does the Model need to provide logic for the View to know what menus to display and how to display them? How does the knowledge that a mouse click (Controller) happened over a tower (View using Model data) get turned into a menu, and then who is in charge of that menu? These struggles were why I wasn’t happy with MVC as the way forward.

Until I had a discussion with Larry, that is. He is way more knowledgeable than I am when it comes to software architecture, and he pointed out that Web MVC is different from MVC.

In Web MVC, the View is simple and dumb.

In a regular MVC, however, the View might have so much logic and data that it rivals the complexity of the Model.

I’ve never thought about the View in this way before! And yet, it seems to make sense. Using StarCraft as an example, the actual game simulation is a complex RTS. Yet, there is a bunch of code to implement the interface that the simulation doesn’t ever care about.

For instance, if you’re playing as the Terran,what happens when you click on an SCV?

![]()

- The SCV in question gets a little circle drawn around it to let you know what unit is selected.

- The Status Display changes to reflect information about the SCV, such as health, armor strength, how many kills it has, etc.

- The command buttons at the bottom right change to reflect actions the SCV can take.

- The portrait changes to static before showing the face of the SCV’s driver.

And until I had this discussion about heavy vs light Views, it never occurred to me that all of those things happen without the game simulation knowing.

If you tell the SCV to move to a specific location, the game cares. If you command the SCV to harvest minerals, the game cares. If you make an SCV repair a bunker, the game cares. Yet, all of the logic dealing with clicking on buttons and units is in the View. It’s only when the player actually does something that results in a command to a specific unit that the game model cares, and even then, it doesn’t know you clicked anything or hit a hotkey. It merely receives a command from somewhere saying “SCV 1 MOVE TO X, Y” or something like that.

Sometimes I struggle with knowing where code should live in my game’s architecture. With the restructuring of my application into a state machine and a good discussion about MVC, the way forward seems clearer. Stop That Hero!‘s player-facing code needs to be a lot more involved than I originally expected. While the game logic is where a lot of the simulation occurs, the interface has a lot of its own logic. It was logic that I knew needed to be implemented, but now I know where the code’s home is.