In the previous post, I reported that levels could be loaded and rendered. So why isn’t it drawing the towers and chests? The short answer is that I didn’t get to them yet, but in all seriousness, it took a little thinking before I could start.

In the original implementation, almost everything was done in a single file of code. The code to draw a tower was:

pHardwareLayer->renderSprite(towerSpriteName, m_towerLocations.at(towerIndex).first * TILE_WIDTH + WORLD_X_START, m_towerLocations.at(towerIndex).second * TILE_HEIGHT + WORLD_Y_START);

TILE_WIDTH and TILE_HEIGHT were each 16, since each tile was 16×16. WORLD_X_START was 0 since it started drawing from the left side of the screen, and WORLD_Y_START was 87 since the UI was drawn at the top.

So depending on which tower I was drawing, I would get the x and y world map offsets, then multiply them by the tile dimensions, and offset by the top left corner of where the world was being rendered.

Why can’t I do the same thing now? Because I didn’t want to hack out everything in one file. A tower is no longer represented by data strewn across different data structures in the game code. A tower is now its own class. A Tower class has these members:

Point m_position;

std::string m_sprite;

int m_type;

int m_status;

There are more variables associated with monster creation and ownership status, but these are the variables relevant to this post.

The Problem

To draw a Tower, I could use the sprite specified by the name in m_sprite and the coordinates in m_position. The problem is that m_position isn’t screen coordinates. It’s map coordinates.

No problem. I’ll change m_position so that it specifies the screen coordinates.

Except m_position is being used in pathfinding, and it is important that it represents a specific tile in the world.

No problem. I’ll just multiply m_position by the tile dimensions, just like in the original implementation.

Er, but, why should the Tower know anything about the tile dimensions? It should only know about towers. Maybe it knows how large it is in terms of tiles, but why should it know how large a tile is? It doesn’t need to, except when it renders a sprite.

No problem. I’ll provide a second Point variable called m_spritePosition which represents its screen coordinates.

That would probably work for stationary towers, but what happens when I need to render moving entities such as Slimes? Unless the on-screen position is mathematically tied to the entity’s position, I can see those two numbers diverging. I could update both pieces of data each time I update one, but what a pain that would be!

The Solution

Create a Sprite class to encapsulate all of it, and let the Sprite class worry about where to render.

Since towers are now encapsulated in their own class, it makes sense that the way I render them (and almost everything else in the game!) should be encapsulated somewhere. The Tower class no longer has its data members polluted with a bunch of members related to sprite drawing, and it doesn’t need to worry about what to do with that data, making its interface and internals a bit cleaner. Also, Sprite classes can be reused for other objects, such as monsters and treasure chests, in a standard way.

To handle the rendering of images, I created a SpriteImage class with the following members and commented explanation:

Point m_position; // The sprite's position

std::string m_imageName; // Name of the sprite in the sprite collection which stores this particular image.

Rectangle m_imageRect; // What rectangular area in that sprite that holds this particular image

IViewPort * m_viewPort; // Explanation to follow.

At first, this solution doesn’t seem to solve the major problem identified above. It looks like the last problem in that the tower’s position and the tower sprite’s position are stored in two different areas.

The trick is that a Sprite defaults to a 1 to 1 mapping between its position and the screen coordinates, but it’s possible to scale it between arbitrary mappings, too! The secret is in m_viewPort.

If a SpriteImage is given a view port, it will scale its position based on what the view port says the scale should be.

How is this useful? Imagine having an 800×600 screen resolution, and you wanted to render a UI button near the bottom right corner. You could make a SpriteImage of a button at position (700, 500), and it would probably work fine.

But then what if you change the screen resolution to 400×300? It’s possible that you’ll port your game to a mobile device with such a resolution. The button would render off of the viewable screen. You’d have to change the button location manually in order to see it at the bottom right corner again. This goes for every image in the game. It could be tedious and error-prone.

Alternatively, you could use a view port that knows the screen resolution is 800×600, and it could be configured to scale based on a percentage. Now, instead of placing a button at (700, 500), you’d set its position at (87.5%, 83.3%). Then, if the screen resolution changes, you simply change the view port, and any sprites associated with it would know the correct scale to use! It’s very powerful and easy to move elements of the screen by horizontal and vertical percentages.

That’s great for rendering sprites anywhere on the screen, but what about my example above? How does a Tower draw on an arbitrarily-sized and arbitrarily-positioned area of the screen, and how does it know where to do so if its position is based on tile position?

As I said, the view port can do arbitrary mappings. In my case, if the world is made up of 50 tiles x 33 tiles, and the area to render everything is 800×528, and it is offset from the top of the screen by (0,87), how would a sprite use this information? Offsetting is easy so I’ll address it first. Wherever a sprite ends up wanting to render itself after scaling, the view port will tell it to move down the screen 87 pixels. As I said before, I use this offset to give room for the UI at the top.

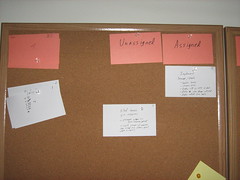

Scaling is almost exactly as it was at the top of the screen. Mapping 50 tiles to 800 pixels requires multiplying by 16, which is the size of each tile. Similarly, 33 maps to 528 with a factor of 16. So if a Tower is set at (50, 33), its going to render at the bottom of the viewable area, whereas a Tower at (25, 0) would be centered at the top just under the UI. Below is a quick example of how I load level data from tiny PNGs.

If you click on the image above, you should be able to get a better idea. The level is described in the small PNG that consists of almost all green pixels and a single white pixel in the middle. When this level data gets loaded, what you see on the screen is a lot of grass tiles and a single tower where the white pixel corresponds. While the PNG is 50×33 pixels, the tower renders in the correct location on the 800×528 view port, even though the tower’s location is in terms of the 50×33 level.

And does it work for moving objects? Absolutely! Let’s say I have a Slime monster located at (2, 3) on the world map, which corresponds to (32, 48) on the screen. When a slime moves to the right, I can’t simply change its position to (3, 3). It would jump the entire width of a tile to get there! Slimes are slow. So why not move it in fractional increments? The scaling still works. A slime moved to (2.1, 3) would correspond with the sprite rendering at (33, 48), which is one pixel over. Technically, it would render at (33.6, 48), but fractional pixels don’t make sense, so for purposes of rendering, we can truncate or round it to the nearest integer.

Again, this view port mapping allows me to do spatial logic at an arbitrary level and not worry about the screen resolution. The only thing I would have to worry about is loading a set of sprites that make sense at lower and higher resolutions. Otherwise, sprites would either overlap or have space in between them. This functionality could also be used to render minimaps and allow zooming and panning.

I like this implementation because the sprites don’t need to have any special logic about what they represent. They just need to know what scale and offsets they’re being rendered at. The object that owns the towers knows where it wants them to go, so it can be in charge of the view port. Tower positions can still be used in pathfinding, and the sprites can still render correctly. The only tricky part might be knowing when I’m loading a sprite at the default scale of the screen resolution and when I’m loading one based on a view port’s scale. To render an image centered at the far right of an 800×600 screen, a sprite at (700, 300) makes sense, but it wouldn’t work if the scale settings assume that positions will be specified in percentages. It would be rendered far off to the right by 700 screen lengths! To specify it in percentages using pixels, (700/800, 300/600) would work.

Also, I’m really happy to have a higher-level sprite class. How did I survive so long without one?