Each week, I’ll go through an exercise from Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games, Third Edition . Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

. Fullerton suggests treating the book less like a piece of text and more like a tool to guide you through the game design process, which is why the book is filled with so many exercises.

You can see the #GDWW introduction for a list of previous exercises.

For this week, I’ll be working on a prototype.

Prototyping

Prototyping is a very important tool for a game designer. It allows you to test a game’s mechanics without worrying about the perfection of the details. Paper prototypes are great because you can get a sense of how well your concept works without code or graphics being needed, allowing you to iterate over a number of ideas very rapidly and inexpensively.

Fullerton offers the following four-step process to make a paper prototype efficiently:

- Foundation: build a representation of the core game play.

- Structure: identify the key rules of the game.

- Formal Details: flesh out the needed rules and procedures to make it a complete game.

- Refinement: polish up the play experience to make it flow.

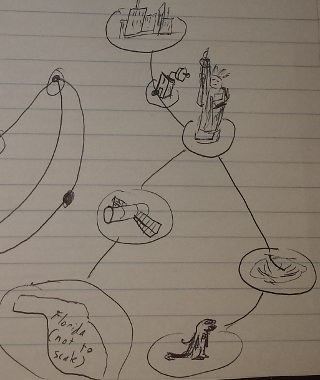

The Initial Concept for Dragon Tail

I’ve been toying around with programming a simulation about segmented creatures recently, and so what easily came to mind is the idea of a segmented tail whipping back and forth to attack the unwary. I eventually came up with the idea of a game about stealing treasure from a dragon.

The goal of Dragon Tail is to steal more treasure than your opponent.

The core activities that can be performed by the player including:

- moving

- picking up and dropping off treasure

- poking and avoiding the dragon’s tail

Ultimately, I would like this to be a real-time mobile game. I’m not sure how the lack of a keyboard will impact the controls of such a game, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I want to work on the initial game design before I worry about implementation details of the finished and polished version.

Foundation

I admit that I struggled with this part. Did I err on the side of not having enough detail, or was I adding rules when I didn’t need them yet?

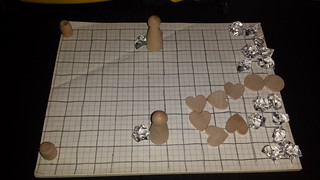

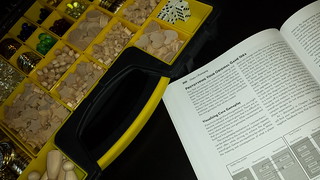

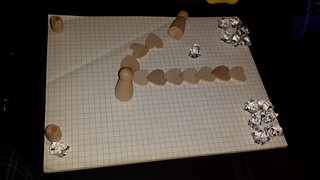

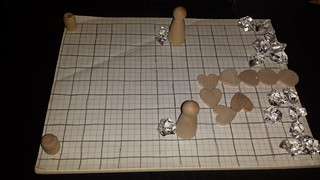

I used some components from my game design prototype toolbox and some graph paper to create an initial scene.

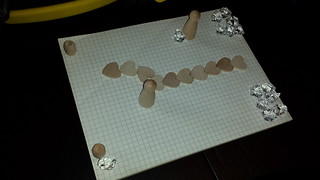

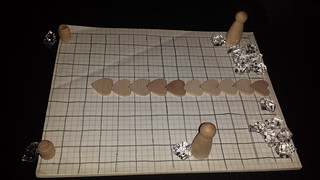

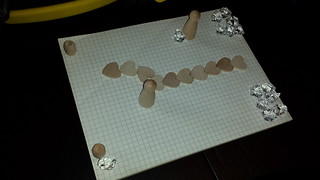

There are two players at one end of the play area, each with their own barrel to signify retrieved treasure. The treasure is at the other end. Also extending from the far end is the dragon tail, implying a dragon protecting treasure but facing the other way.

Right now, as this is a paper prototype, the game will be turn-based. A player can run by moving between adjacent spots.

If the player is next to a treasure, he or she can pick up a single piece of treasure and carry it. While carrying treasure, movement is slowed. The player can then attempt to bring the treasure back to the barrel.

So far, it isn’t much, but it’s a start. There are a lot of questions. How far can a player move in a single turn? How much slower is the player made to move when carrying treasure? How much is treasure worth? What about the dragon tail?

But it isn’t a small thing I’ve done. Retrieving treasure is the main activity, and I’ve established that treasure can only be taken one piece at a time. Or am I being premature in making that a rule at this point?

If players can’t collect all the treasure at once, treasure-stealing is a drawn out affair. On the other hand, if the player is allowed to collect multiple pieces of treasure at once, perhaps the encumbrance increases and movement is slowed progressively. Steal one piece, and you can move relatively faster than if you steal five pieces.

Perhaps these are questions best left for the Structure step, and for now the idea of multiple pieces of treasure and the idea of running and collecting them is enough to identify the core game play.

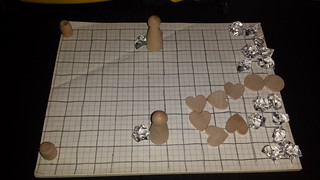

Already I am thinking about how the players will interact with each other and the dragon tail. Poking the dragon’s tail forces it to swing in the other direction.

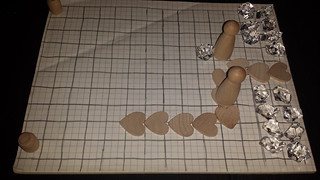

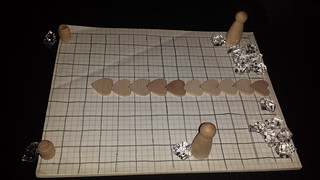

In this shot, one player is returning with treasure, but the other player has poked the tail, which has started whipping slowly toward the first player.

How the tail moves sounds like a Structure issue as well, but the idea that there is a tail that moves away from the player who poked it and can eventually hit the opponent might be enough here.

Does the tail merely knock him or her over temporarily? Does it kill the player and force a respawn? What happens to the treasure if it was being carried?

As I said, I struggled here with trying to keep the prototype in the Foundation step. Fullerton asks you to try to play your core game play on your own in order to see if the basic concept is worth pursuing while avoiding the temptation to add rules unless they are absolutely necessary. But how do I play this game without putting some rules in place to dictate how I can play it in the first place?

So far, I know I have some number of treasure pieces, a whipping tail, and competing players who can move, carry treasure, and poke the tail. The players can also be hit by the tail with some currently unknown consequences.

It’s probably time for some structure.

Structure

Where do I start? I think the movement of the players is a good place, as moving is going to be a key part of the game play. It allows you to make progress towards collecting treasure and dodge the swinging dragon tail.

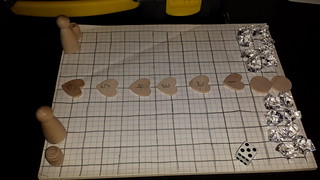

I divided the play area into a grid of squares. A player can move between adjacent squares and is allowed to move up to three squares each turn. When carrying treasure, a player is encumbered and can move only one square.

Treasure can be collected one piece at a time. There. Now it feels OK to make this rule. How many pieces are there? Maybe specifying it now is too early. There are multiple pieces available to both players. Maybe that’s enough for now.

How does a player obtain a piece of treasure? Instead of moving, a turn can be used to pick up a piece. Dropping off the piece in the barrel, however, is automatic and does not require more than being adjacent to it.

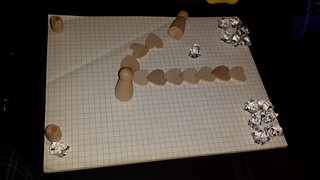

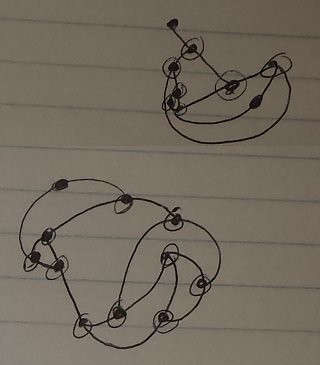

And the tail? It’s segmented, represented by the wooden heart pieces. As you get further down the tail, each segment attaches to the end of the previous. Each segment can turn 90 degrees left or right, which affects the positioning of the remainder of the tail segments.

For example, if a segment is turned to the right, the rest of the tail moves to attach to the new position of the end of that segment. Each turn, the next segment down the line will also turn 90 degrees, until all are rotated 90 degrees. Then the segment furthest up the tail rotates back to the original orientation, and the later segments likewise take turns rotating back into place.

What causes the first segment to rotate? A player can be adjacent to the tail segment and use the turn to poke it.

At the poke site, the segment will turn 90 degrees away from the player.

In this way, each turn the tail will get closer and closer to the opponent, potentially blocking movement depending on how far up the tail it was poked.

A poke at the far end of the tail will result in only one segment rotating 90 degrees for one turn, but a poke at the treasure end will have the entire tail curling, making it almost impossible to avoid.

And when the tail hits a player, I want it to cause problems. It will knock over the player for a turn and smack the treasure back to the pile. The player can use the next turn to get back up.

Right away, I can see an issue with the interaction with the tail. What happens when a player gets knocked over near the poked segment? The tail will extend through the same square for multiple turns, so getting up the next turn means standing on the tail. How does that work? I suppose I didn’t specify that the players can’t walk through spaces that the tail segments are on, but now I need a way for the player to get up ON a tail segment? Something needs to change here.

Also, since it takes multiple turns for the dragon tail to whip around, it can effectively trap one player for a very long time. Getting trapped is potentially devastating.

So now I have more questions: can you poke a tail segment when the tail is in the process of whipping, or can you only poke a tail at rest? Can a player carrying treasure poke a tail?

Let’s assume one can poke a tail while holding treasure and if the tail is already whipping. Here, the player that was trapped can poke an earlier segment and cause the tail to come dangerously close to the opponent.

And now the revenge! The treasure is returned as the original player is knocked over by the tail.

With this interaction, I worry that it will be impossible to collect treasure as each player tries to poke the tail in turn and cause problems for each other. Even when progress is made, it can be taken away too easily.

I think that the movement and treasure-collecting parts are workable, but the tail interaction is in need of some help.

If both players ignored the tail and simply collected the treasure, there would be no challenge. Whoever went first would be guaranteed to win.

I have a tendency to try to make games that don’t have any random elements in them, but then it is very hard to make something that cannot be easily solved.

I imagine that there should be a way to avoid getting hit by the tail. If you are carrying treasure, you can drop it, and the treasure acts as an obstacle that the tail can wrap around. Maybe. I’ll keep that thought for later.

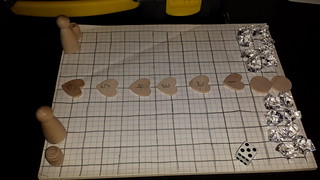

Perhaps this game needs the tail to move on its own? Rolling a die can indicate if the tail should move, which part should move, and in which direction. Maybe the tail should be only six segments long to match the six sides of a die.

Maybe I should explore the idea of the tail being a pain to navigate around. Instead of having it rotate segments each turn, it could stay in place until the next time the die roll changes it.

After both players have made a move, the die is rolled to indicate which tail segment will be rotated next. Roll the die again to determine which direction it should rotate. Rolling a 3 or less should rotate it clockwise, and 4 or more should rotate it counter-clockwise.

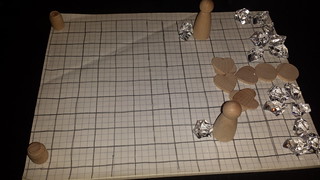

Hmm, the tail shouldn’t kink, since a later tail segment is supposed to attach to the end of the first, and a kink means that the segments are on top of each other. But maybe I’ll let it happen and see how it plays out. Perhaps the tail will curl around itself at times?

If a segment rotates, do the later segments rotate with it, or do they stay in their orientation and merely attach at the new end? I think the latter ends up being easier to manage.

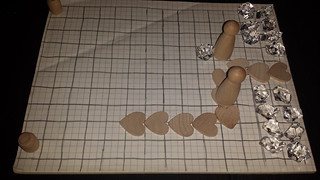

Well, this tail really did curl in on itself. Will it constantly get that way? I need to playtest some more to know, but at least on the next die roll I see that it successfully uncurled a little.

The next die roll after that even did what I hoped it would do: cause the tail to block access to the treasure.

Even though the players have been able to move through unscathed so far this play session, I think I can see the tail movement has added a sense of fear to the game. What if it swings out and hits me? What if I can’t get to the treasure I was aiming for and now have to go around the tail, losing precious time? Oh, phew! I have some relief that the tail curled in on itself, although I’d rather it smack the other player.

OK, so kinks in the tail aren’t a terrible problem. What I also like is that a single rotation near the beginning of the tail can cause it to swing drastically. The only real issue I’ve seen is that I have hard time telling which segment is which when it starts kinking. Maybe labeling them with numbers would make it easier?

Hmm, am I no longer thinking of Structure and jumping ahead to Formal Details?

Formal Details

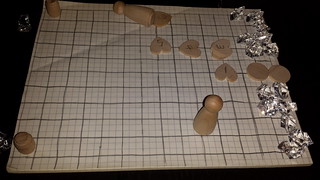

After playtesting with someone else, I found that the kinks in the tail manifest as a confusing mess that make it hard to understand what is happening. Rather than seeing it as something that can potentially swing out at any moment and so can be anticipated, the entire concept is chunked as a random event that will be dealt with if anything happens, but otherwise can be ignored. I’m not happy with how unimportant this aspect seems to a player’s turn.

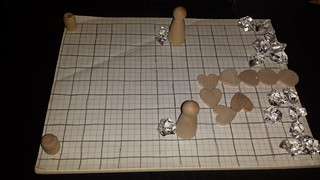

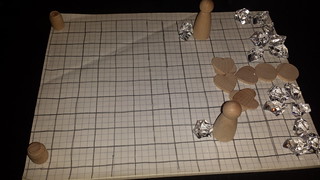

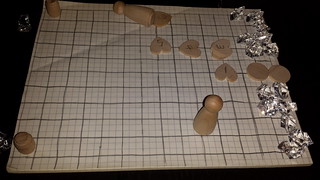

I numbered the tail segments to make it easier to understand which was which, but I also found that the tail segments were hard to align, partly because the wooden pieces I was using didn’t fit nicely on the grid. So I made them fit.

I spread out the tail segment so that each segment straddled four different grid squares. Not only does this help make it easier to move the segments around when one of them rotates, but it also clarifies where a segment is. Before this change, some segments seemed to be in one space, but when rotated, they bumped up against other segments and seemed to be in a completely different space or to cross two spaces. It was difficult to tell if a player had been hit by the tail or if the player could poke the tail.

I tried testing the poking mechanic. What if you can poke at the end of your movement, but you can’t poke if you are carrying treasure? Well, during one session, one player got hit twice and was trapped while carrying treasure and was forced to wait until the tail moved, which might not happen for many turns. Frustrating, but not fun.

Also, can you poke when getting up after being knocked down? I decided that when you are knocked down, you are pushed to the nearest free space of your choice. After that, however, your opponent might be running off with treasure, and if all you can do is get up on your turn, it feels quite futile.

In light of both of these situations I decided that poking at the end of any turn was valid. If you get knocked down, on your next turn you can poke the tail to try to hit your opponent to prevent him or her from getting too far ahead. I think it will help with the balance. Only playtesting will tell, of course.

Refinement

This step can last many iterations, and I am going to run out of time before I can consider this game done enough. It is here that any features and rules that aren’t core to the game can be experimented with to see if it creates a compelling experience.

What follows are some of the concerns I identified.

How big should the play area be? I had graph paper and tried to center the grid of 3×3 squares, but what if the paper was smaller or bigger, and in any one dimension to boot? If it is too small, the tail will impact the play area a lot more, but if it is too big, then players can choose to hug the walls at the expense of using up more moves and taking longer to avoid the tail.

I noticed that whenever the sixth segment needs to rotate that it is inconsequential. Is this situation similar to the dragon tail losing a turn, so to speak, or should there be a seventh piece? Which is better for the enjoyment of the game, added risk or the equivalent of Monopoly’s Free Parking?

The interaction with the tail also feels like it isn’t as finished as it could be. Instead of being a significant piece of the game, at times it feels like it is nothing more than a completely random event. That is, players are running after treasure and usually can forget that there is a tail in the game at all, and suddenly a tail hits one.

And when one does get knocked down, where does he or she get moved? Letting the player choose the nearest open space is ok, but if it was a video game, I feel like it should be deterministic and handled automatically by the game. So, what’s the simple and easy rule for displacement by the tail?

I learned during playtesting that the game is slow. Well, how do I solve this issue? It takes 16 moves to get to the treasure, pick it up, and bring it back to the barrel. Moving three spaces at a time might be fine, although now that the tail segments take up a 2×2 area it could be tweaked. Perhaps moving two spaces at a time instead of only one when carrying treasure might help? Then it would only take about 10 moves, especially if I allow the player to pick up the treasure at the end of a turn instead of making it a separate turn on its own.

Instead of bringing the treasure back to the barrel, just bring it back to the other end of the play area. So whenever treasure crosses the last set of squares it’s considered collected by that player. In this way, there isn’t a faster treasure to collect, and so if you find yourself on the other side of the dragon tail due to necessity, it won’t slow you down as much. You just have to move back to the left, not left and down to a specific spot.

There could also be less treasure. I placed 16 pieces because they fit, but having less can improve the time to play the game. Also, an uneven number guarantees that there will be a contention. One player will get to the last piece first, and so the other player then wants to manipulate the tail in order to try to prevent the first player from winning. But how many pieces of treasure should there be in the game? I can do some playthroughs and time it, or see how long it takes for a single treasure to be collected and multiply it by how long I want the game to take.

Hmm, the ending is quite unsatisfying. The player without the last treasure piece can’t do much to interfere with the other player other than poke the dragon tail, which might be far enough away that by the time he or she gets close enough to do so, the player with the treasure is too far out of reach.

That sense of despair is a symptom of the lack of meaningful player interaction, which I think is a big concern. How much of a change do I need to make to address it?

An example of a minor change is changing the effect of poking the tail. What if it doesn’t just turn the segment 90 degrees but allows the player to choose the new orientation? Would doing so make it a lot easier to have an impact on the game?

A bigger but related change might be if poking the tail allows the player to move the tail segment one space adjacent. Of course, if segment is moved, it has to be a valid connection to the parent tail segment, so how will it be resolved without being too complicated for the player to figure out?

A major change would be the introduction of obstacles. What if you could push boulders around, which not only act as obstacles for the players but also for the tail, which can wrap around them? Sounds good, but now there are number of questions to answer. How do boulders get added to the play area? When are they added? Can they be destroyed? Are they permanent obstacles, or can a player move one? If so, how far? Can multiple boulders in a row be pushed at once, or do they prevent the player from pushing them in that case? If the latter, is it possible to get stuck permanently between multiple boulders? What happens when you push the boulders in front of the treasure and block access to it? What happens if you push the boulders across the starting area?

Maybe treasure isn’t carried but is pushed and acts the same as the boulders described above?

Can there be fool’s gold? That is, sometimes you collect treasure only to find that it doesn’t count towards your score. Maybe it’s a random chance, such as rolling a die for each treasure you captured and trying not to roll a 1.

Or each treasure you collect has you draw a card from a deck. At the end of the game, even though you collected more treasure, there’s a chance your opponent might win because you discover your treasure is fool’s gold when everyone is asked to reveal their treasure cards. It might make it a way for people to catch up at the end. So, how many cards are there? How many fool’s gold cards are in the full treasure card deck? Is it constant between games, or is it like Saboteur in which the number of potential saboteurs is different from one session to the next?

As you can imagine, exploring the playspace here is a very big job. Testing a single rule change at a time can get tedious, but how else will you know what works? I’m reminded of the development of Steambirds: Survival, which Daniel Cook described as finding the Goldilocks Zone of games, the playspace in which the game is enjoyable.

Many attempted ideas will fail, but if you explore enough variations, you can find what works much more quickly.

Exercise Complete

This post is about 4,000 words long, and I tried to capture how the process went. And of course, I still have a lot of work to do.

I didn’t do a very good job of working on this prototype in these four separate stages. I sometimes found myself thinking about details when I was supposed to be working on fundamentals, or refining some structure instead of refining the details.

So while the above might show a somewhat organized thought process, the reality of it was that there was a bit of messiness to it. That said, the four steps did help me think about the nature of the change I was making at any given point, which helped me restrain from thinking about features when I should be focusing on rules. I think the attempt at following these steps helped me create this game much more rapidly than I might have otherwise.

If you participated in this exercise on your own, please comment below to let me know, and if you wrote your own blog post or discuss it online, make sure to use the hashtag #GDWW.

This post concludes my GDWW exercise posts. I’ll be publishing a book review next week. Thank you for following along, and I look forward to seeing your prototypes!